Click the link below the picture

.

I love simple questions that wind up having complicated—or at least not straightforward—answers. Astronomers twist themselves into knots, for example, trying to define what a planet is, even though it seems like you’d know one when you see it. The same is true for moons; in fact, the International Astronomical Union, the official keeper of names and definitions for celestial objects, doesn’t even try to declare what a moon is. That’s probably for the best because that, too, is not so easy.

What about stars, though? Do they also confound any sort of palatable definition?

In a very broad sense, a star is simply one of those twinkling points of light you can see in the night sky. But that’s not terribly satisfying in either lexicological or physical terms. After all, we also know the sun is a star—but, by definition, we never see it in Earth’s night sky, and it’s certainly not a dot (unless you’re viewing it from well past Pluto, that is).

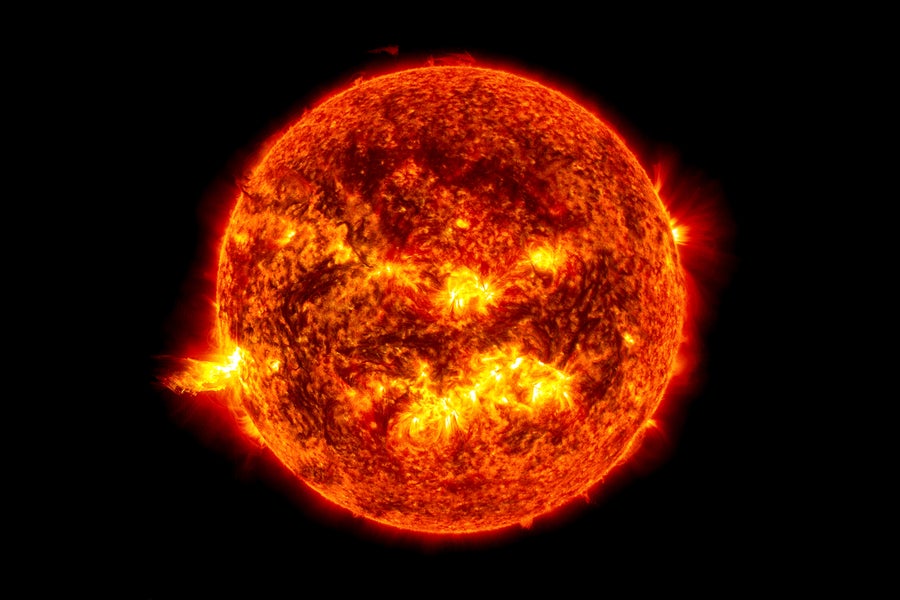

If such a basic definition leaves us a bit dry, then perhaps we can do better. From centuries of scientific observations and theoretical physics, we can say more. Stars are massive, hot and roughly spherical. They’re held together by their own gravity, and they consist of plasma (gas heated so much that electrons are stripped from its constituent atoms). And, of course, they’re luminous. They shine, which is probably their most basic characteristic.

That’s descriptive, certainly, but still doesn’t really tell us what a star is. What makes one different from, say, a planet? Can there be a smallest star or a biggest one?

To sensibly answer such questions, we need to understand the core mechanism that makes a star luminous in the first place. Then we can use that understanding to better define what is or isn’t a star.

Historically, astronomers were in the dark about this for quite some time. Many mechanisms were proposed, but it wasn’t until the early 20th century that quantum mechanics came to the rescue and introduced humanity (for better or worse) to the concept of nuclear fusion. In this process, subatomic particles such as protons and neutrons—and even entire atomic nuclei—could be smashed together, fusing to form heavier nuclei and releasing an enormous amount of energy.

In a star’s core, fusion takes terrific temperature and pressure that is provided by the crushing gravity of the star’s overlying mass. For a star to be relatively stable, the outward force of the energy generated by fusion in its core must be balanced by the inward pull of the star’s gravity.

There are a couple of different pathways for fusion to occur in stars like the sun, but in the end they both yield essentially the same result: four hydrogen nuclei (each a single proton) plus various other subatomic particles fuse together to form a helium nucleus, and this process blasts out a lot of high-energy radiation as a byproduct. In the sun, this process converts about 620 million metric tons of hydrogen into helium every second. That creates enough energy to, well, power a star.

.

A view of our sun, as seen by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory. NASA/Goddard/SDO

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Apr 18, 2025 @ 04:06:54

Interesting post.

LikeLike

Apr 18, 2025 @ 08:43:58

Thank you sir! Our sun is like a grain of sand in the universe.

LikeLiked by 1 person