Click the link below the picture

.

For years, scientists have viewed cancer as a localized glitch in which cells refuse to stop dividing. But a new study suggests that, in certain organs, tumors actively communicate with the brain to trick it into protecting them.

Scientists have long known that nerves grow into some tumors and that tumors containing lots of nerves usually lead to a worse prognosis. But they didn’t know exactly why. “Prior to our study, most of the focus has been this local interaction between the nerve [endings] and the tumor,” says Chengcheng Jin, an assistant professor of cancer biology at the University of Pennsylvania and a co-author of the study, which was published today in Nature.

Jin and her colleagues discovered that lung cancer tumors in mice can use these nerve endings to communicate way beyond their close vicinity and send signals to the brain through a complex neuroimmune circuit. They also confirmed the circuit exists in humans.

Setting up this circuit starts with a process called innervation, in which lung tumors wire themselves into the vagal nerves—the internal information highway that connects the vital organs to the brain. Within this highway, Jin’s team identified a specialized group of sensory neurons that communicate directly with the central nervous system. “Our study suggests that the tumor actually hijacks these existing pathways to promote itself,” explains Rui Chang, an associate professor of neuroscience at the Yale School of Medicine and a co-author of the study.

When a tumor develops, it employs vagal neurons to send signals screaming up to the nucleus of the solitary tract—the region in the brain stem that, under normal circumstances, keeps functions such as blood pressure, heart rate or digestion in check. The signal sent by the tumor exploits this system, much like malicious code used by a hacker.

Instead of recognizing the tumor as an invader that needs to be destroyed, the brain processes the signal and activates the sympathetic nervous system, mainly known as the driver of the fight-or-flight response. This sympathetic surge is caused by the release of noradrenaline, which, in the context of cancer, has catastrophic consequences.

The noradrenaline is released directly in the tumor’s immediate neighborhood, where it attaches to macrophages—the frontline cells of the immune system that identify, eat, and destroy threats. The macrophages are covered in docking stations called β2 adrenergic receptors, which normally tell the cells when to be aggressive and when to “chill,” preventing the immune system from destroying healthy cells. When the noradrenaline released by the brain-controlled nerves binds to these receptors, it effectively reprograms the macrophages to switch sides.

In this suppressed state, they start releasing chemical signals that act as a “do not disturb” sign for the rest of the immune system. This neutralizes one of the body’s most effective weapons: T cells, the specialized assassins that physically kill tumor cells. Because the brain has ordered the macrophages to create an immunosuppressive shield, the T cells lose their energy, stop multiplying, and fail to recognize the cancer as a threat.

“The authors characterized an entire bidirectional tumor-neural pathway that promotes tumor growth, with huge relevance to human health,” says Catherine Dulac, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at Harvard University, who was not involved in the study.

Jin and her team also looked for ways to stop tumors from talking to the brain. By mapping this loop from the lung to the brain and back again, the researchers identified several new places where they could “cut the wire.” The study showed that blocking any part of the brain-tumor circuit reawakened the immune system.

“Obviously, the perspective for application to cancer treatment is extremely promising,” Dulac says. Jin and Chang say we’re still rather far away from translating their findings into therapeutic strategies, however.

“What we are talking about is going from a mouse model to human. I think there’s still a long way to go,” Chang says.

.

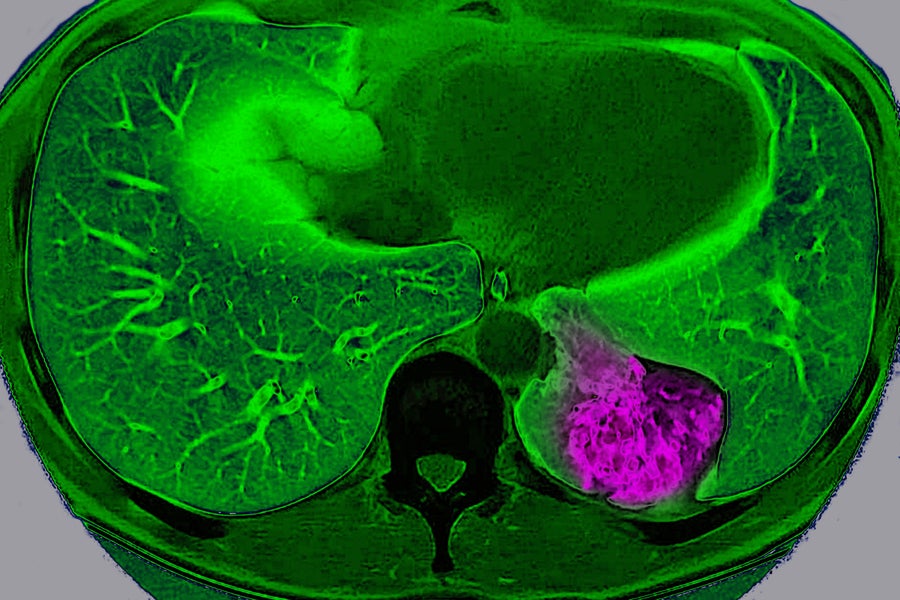

Lung cancer on the left pulmonary lobe, seen on a radial section MRI scan of the chest. BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lung-cancer-hijacks-the-brain-to-trick-the-immune-system/

.

__________________________________________

Feb 07, 2026 @ 05:30:40

Simply amazing 👏 thank you for sharing this amazing EARLY scientific breakthrough

LikeLike

Feb 07, 2026 @ 05:31:19

Will reblog this article 😀

LikeLike

Feb 07, 2026 @ 07:53:37

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Feb 07, 2026 @ 07:54:52

Thanks for your comment!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Feb 07, 2026 @ 08:14:03

LikeLike

Feb 07, 2026 @ 08:17:59

L

ALSO YOU CAN SEE THIS TAKE OVER WITH THE Protozoa Toxoplasma gondii: Fatal Attraction Phenomenon in Humans – Cat Odour Attractiveness Increased for Toxoplasma-Infected Men While Decreased for Infected Women

By Flegr Et. AL

LikeLike

Feb 07, 2026 @ 08:19:28

“The most impressive effect of toxoplasmosis is the “fatal attraction phenomenon,” the conversion of innate fear of cat odour into attraction to cat odour in infected rodents. While most behavioural effects of toxoplasmosis were confirmed also in humans, “

LikeLike

Feb 07, 2026 @ 08:23:01

I have a friend that has it in his eye 👁 😳 and every year the parasite finds a way to escape immune surveillance and for a week he has to wear sunglasses 👓 and take medications until the parasite goes dormant. Got it from playing in a sandbox that was frequented by the wild cats 🐈 in the area. He is a great 👍 sport about it, ALL in All, he is like ” I still have my vision”. Great 👍 friend

LikeLike

Feb 07, 2026 @ 08:23:41

“Toxoplasma gondii, a common parasite, causes ocular toxoplasmosis, an inflammation of the retina (retinochoroiditis) that leads to blurry vision, floaters, and sensitivity to light, potentially causing permanent vision loss, especially if it affects the central retina. “

LikeLike