Click the link below the picture

.

Key Takeaways

-

The Sun is by far the dominant body in our Solar System in many ways: in terms of size, mass, and energy, but also for generating the effects of space weather through the rapid motion of many charged particles.

-

Most commonly, we learn about solar flares and coronal mass ejections, and those events do indeed create the majority of auroral displays that occur here on Earth: the Aurora Borealis and the Aurora Australis, in particular.

-

However, there’s a third class of space weather event that is much rarer: solar radiation storms. The last major one was in 2003, but a new one in January of 2026 just triggered a spectacular auroral show. Here’s why.

Starting on the night of January 19, 2026, planet Earth was treated to a global show that had only been seen once before in the 21st century: a spectacular auroral display that wasn’t triggered by a solar flare or by a coronal mass ejection, but instead by a completely different form of space weather known as a solar radiation storm. Whereas solar flares normally involve the ejection of plasma from the Sun’s photosphere and coronal mass ejections typically involve accelerated plasma particles from the Sun’s corona, a solar radiation storm is simply an intensification of the charged ions normally emitted by the Sun as part of the solar wind. Only, in a radiation storm, both the density and speed of the emitted particles get greatly enhanced.

We’re currently still in the peak years of our current sunspot cycle: the 11-year solar cycle that’s been tracked for centuries, where “peak years” see 100+ sunspots on the Sun while “valley years” see a largely featureless Sun. While several notable auroral displays have graced Earth in recent years, there’s only been one other severe (S4 or higher-class) solar radiation storm this century: back in 2003. Whereas most space weather events take around 3-4 days to traverse the Sun-Earth distance, the particles ejected from the Sun early on January 19, 2026 (UTC) were already triggering spectacular auroral displays less than 24 hours later. Here’s the science of how it all happened, and what dangers — and displays — such events hold in store for our world.

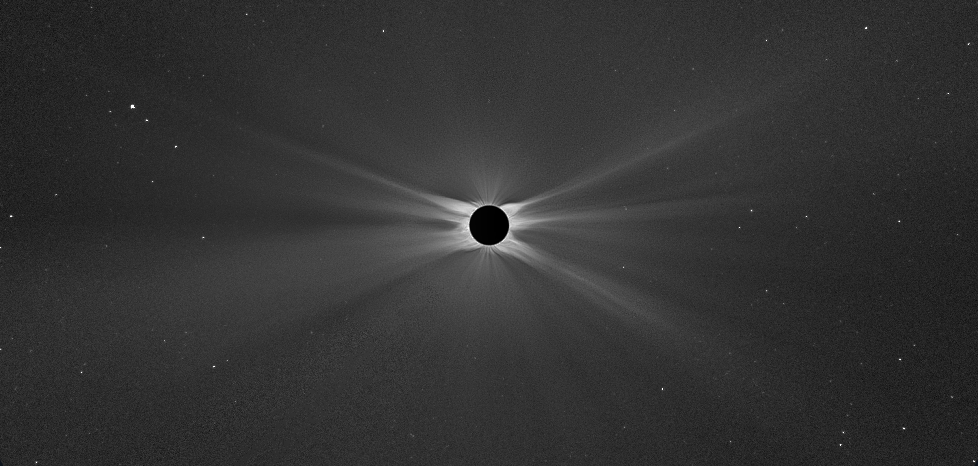

Credit: Martin Antoš, Hana Druckmüllerová, Miloslav Druckmüller

The first thing you should understand — and not only people, but even most physicists, don’t fully appreciate this — is that the Earth, and all of the planets in the Solar System, are actually inside the atmosphere of the Sun. We usually think about the Sun as being a ball of plasma with a wispy, extended atmosphere and a halo-like corona surrounding it, but those are only the locations where the plasma density is the greatest. In reality, the Sun is a powerful enough, hot enough engine that it fills everything inside our heliosphere, which extends out to beyond the orbits of Neptune and Pluto, with that hot, ionized plasma.

While we typically only view the extended atmosphere of the Sun under favorable viewing conditions, like during a total solar eclipse from Earth, or from up in space with the advent of a Sun-blocking coronagraph, we’ve been able to track a wide variety of its effects. We know that it produces light, sure, but it also consistently produces a stream of ions, mostly protons but also electrons, heavier atomic nuclei, and even small amounts of antimatter, known as the solar wind. That solar wind is guided by the Sun’s magnetic field, which is driven by internal processes inside the Sun, and particularly energetic outbursts come when magnetic field lines “snap” and reconnect at, near, just outside, or even fully inside the Sun’s photosphere.

Credit: NASA/SDO

When those magnetic reconnection events occur internally, normally where sunspots are located, a solar flare often results. When those reconnection events occur externally, fully outside of the Sun’s photosphere, a coronal mass ejection often results. But when those reconnection events occur outside the surface but before you reach the corona, it typically just rapidly accelerates the charged particles that exist in that region outside of the photosphere. That creates the conditions for what’s known as a solar radiation storm, which can then be accompanied — usually afterwards — by either a solar flare (if the reconnection propagates backwards to the Sun’s interior) or a coronal mass ejection (if the reconnection propagates forwards to the Sun’s corona).

The 2003 event, known as the Halloween solar storms because they peaked from mid-October to early November, included both solar flares and coronal mass ejections, including the strongest solar flare ever recorded by the GOES (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite) system, and that was the last severe solar radiation storm that affected the Earth. On January 19, 2026, another one occurred, and it indeed was also followed up by an X-class solar flare and a coronal mass ejection. However, solar flares and coronal mass ejections are common; what was highly uncommon was the solar radiation storm, and the ultra-fast (and large flux of) solar wind particles that came towards Earth.

Above, you can see a graph of the solar wind speed just prior to the start of the solar outburst that created the radiation storm. Note that, prior to the initiation of the storm, the solar wind speed was relatively stable and typical: at around 250-300 km/s, or about 0.1% the speed of light. Under these conditions, it takes the solar wind approximately 5-7 days to traverse the Earth-Sun distance. During normal circumstances, we don’t see a major auroral event, and that’s due to the combined facts that:

-

The Sun’s magnetic field is weak,

-

The Earth’s magnetic field (at least close to Earth’s surface) is strong,

-

There’s only a low density of solar wind particles, and they move at relatively slow speeds,

-

making Earth’s magnetic field effective at diverting the majority of solar wind particles away from the planet.

.

This photograph shows the Aurora Borealis as taken over Loch Calder in northern Scotland on the night of January 19, 2026. Although this was the largest solar radiation storm experienced on Earth since 2003, the aurora appeared brilliantly for only brief periods of time, due to the alignment of the Earth’s and Sun’s magnetic field only being favorable for a period of approximately two hours during the event. Credit: David Proudfoot/BlueSky

This photograph shows the Aurora Borealis as taken over Loch Calder in northern Scotland on the night of January 19, 2026. Although this was the largest solar radiation storm experienced on Earth since 2003, the aurora appeared brilliantly for only brief periods of time, due to the alignment of the Earth’s and Sun’s magnetic field only being favorable for a period of approximately two hours during the event. Credit: David Proudfoot/BlueSky

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment