Click the link below the picture

.

Amy Bies was recovering in the hospital from injuries inflicted during a car accident in May 2007 when routine laboratory tests showed that her blood glucose and cholesterol were both dangerously high. Doctors ultimately sent her home with prescriptions for two standard drugs, metformin for what turned out to be type 2 diabetes and a statin to control her cholesterol levels and the heart disease risk they posed.

The combo, however, didn’t prevent a heart attack in 2013. And by 2019, she was on 12 different prescriptions to manage her continued high cholesterol and her diabetes and to reduce her heart risk. The resulting cocktail left her feeling so terrible that she considered going on medical leave from work. “I couldn’t even get through my day. I was so nauseated,” she said. “I would come out to my car in my lunch hour and pray that I could just not do this anymore.”

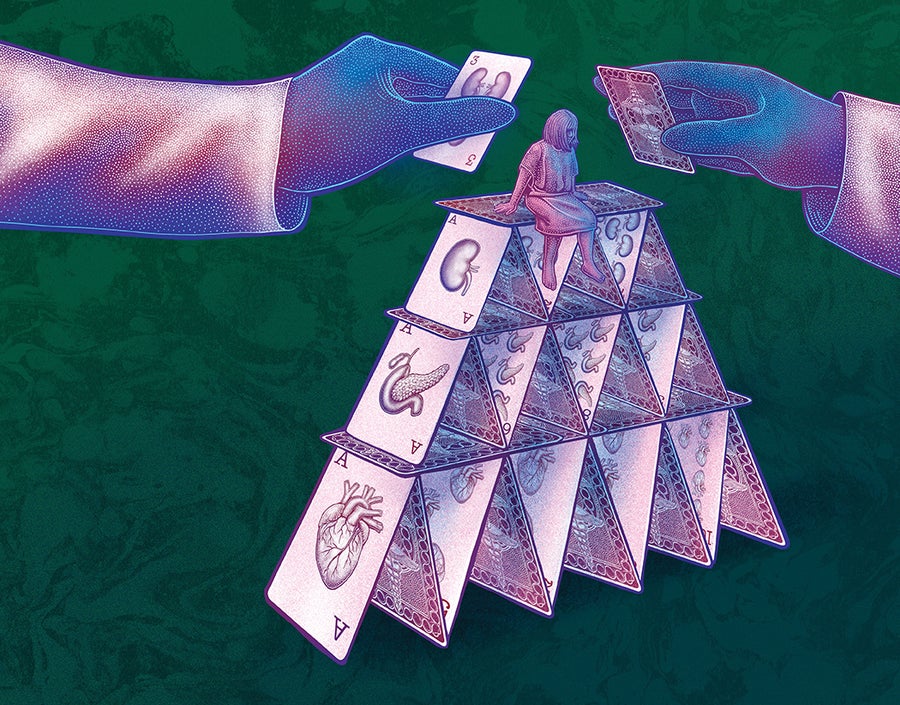

Medical researchers now think Bies’s conditions were not unfortunate co-occurrences. Rather, they stem from the same biological mechanisms. The medical problem frequently begins in fat cells and ends in a dangerous cycle that damages seemingly unrelated organs and body systems: the heart and blood vessels, the kidneys, and insulin regulation, and the pancreas. Harm to one organ creates ailments that assault the other two, prompting further illnesses that circle back to damage the original body part.

Diseases of these three organs and systems are “tremendously interrelated,” says Chiadi Ndumele, a preventive cardiologist at Johns Hopkins University. The ties are so strong that in 2023 the American Heart Association grouped the conditions under one name: cardio-kidney-metabolic syndrome (CKM), with “metabolic syndrome” referring to diabetes and obesity.

The good news, says Ndumele, who led the heart association group that developed the CKM framework, is that CKM can be treated with new drugs. The wildly popular GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as Wegovy, Ozempic, and Mounjaro, target common pathology underlying CKM. “The thing that has really moved the needle the most has been the advances in treatment,” says Sadiya Khan, a preventive cardiologist at Northwestern University. Although most of these drugs come only in injectable forms that can cost several hundred dollars a week, pill versions of some medications are up for approval, and people on Medicare could pay just $50 a month for them under a new White House pricing proposal. The appearance of these drugs on the scene is fortunate because researchers estimate that 90 percent of Americans have at least one risk factor for the syndrome.

More than a century before Bies entered the hospital, doctors had noticed that many of the conditions CKM syndrome comprises often occur together. They referred to the ensemble by terms such as “syndrome X.” People with diabetes, for instance, are two to four times more likely to develop heart disease than those without diabetes. Heart disease causes 40 to 50 percent of all deaths in people with advanced chronic kidney disease. And diabetes is one of the strongest risk factors for developing kidney conditions.At present, around 59 million adults worldwide have diabetes, about 64 million are diagnosed with heart failure, and approximately 700 million live with chronic kidney disease.

The first inkling of a connection among these disparate conditions came as far back as 1923, when several lines of research started to spot links among high blood sugar, high blood pressure, and high levels of uric acid—a sign of kidney disease and gout.

Then, several decades ago, researchers identified the first step in these tangled disease pathways: dysfunction in fat cells. Until the 1940s, scientists thought fat cells were simply a stash for excess energy. The 1994 discovery of leptin, a hormone secreted by fat cells, showed researchers a profound way that fat could communicate with and affect different body parts.

Since then, researchers have learned that certain kinds of fat cells release a medley of inflammatory and oxidative compounds that can damage the heart, kidneys, muscles, and other organs. The inflammation they cause impairs cells’ ability to respond to the pancreatic hormone insulin, which helps cells absorb sugars to fuel their activities. In addition to depriving cells of their primary energy source, insulin resistance causes glucose to build up in the blood—the telltale symptom of diabetes—further harming blood vessels and the organs they support. The compounds also reduce the ability of kidneys to filter toxins from the blood.

Insulin resistance and persistently high levels of glucose trigger a further cascade of events. Too much glucose harms mitochondria—tiny energy producers within cells—and nudges them to make unstable molecules known as reactive oxygen species that disrupt the functions of different enzymes and proteins. This process wrecks kidney and heart tissue, causing the heart to enlarge and blood vessels to become stiffer, impeding circulation and setting the stage for clots. Diabetes reduces levels of stem cells that help to fix this damage. High glucose levels also prod the kidneys to release more of the hormone renin, which sets off a hormonal cascade critical to controlling blood pressure and maintaining healthy electrolyte levels.

At the same time, cells that are resistant to insulin shift to digesting stored fats. This metabolic move releases other chemicals that cause lipid molecules such as cholesterol to clog blood vessels. The constriction leads to spikes in blood pressure and heightens a diabetic person’s risk of heart disease.

The circular connections wind even tighter. Just as diabetes can lead to heart and kidney conditions, illnesses of those organs can increase a person’s risk of developing diabetes. Disruption of the kidneys’ renin-angiotensin system—named for the hormones involved, which regulate blood pressure—also interferes with insulin signaling. Adrenomedullin, a hormone that increases during obesity, can also block insulin signaling in the cells that line blood vessels and the heart in humans and mice. Early signs of heart disease, such as constricted blood vessel,s can exhaust kidney cells, which rely on a strong circulatory system to filter waste effectively.

The year before Bies’s car accident, when she was in her early 30s, her primary care doctor diagnosed her with prediabetes—part of metabolic syndrome—and recommended changes such as a healthier diet and more exercise. But at the time, the physician didn’t mention that this illness also increased her risk of heart disease.

Not seeing these connections creates dangers for patients like Bies. “What we’ve done to date is really look individually across one or two organs to see abnormalities,” says nephrologist Nisha Bansal of the University of Washington. And those narrow views have led doctors to treat the different elements of CKM as separate, isolated problems.

For instance, doctors have often used clinical algorithms to figure out a patient’s risk of heart failure. But in a 2022 study, Bansal and her colleagues found that one common version of this tool does not work as well in people with kidney disease. As a result, those who had kidney disease—who are twice as likely to develop heart disease as are people with healthy kidneys—were less likely to be diagnosed and treated in a timely manner than those without kidney ailments.

.

Jennifer N. R. Smith

Jennifer N. R. Smith

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment