Click the link below the picture

.

Rachel Feltman: For Scientific American’s Science Quickly, I’m Rachel Feltman.

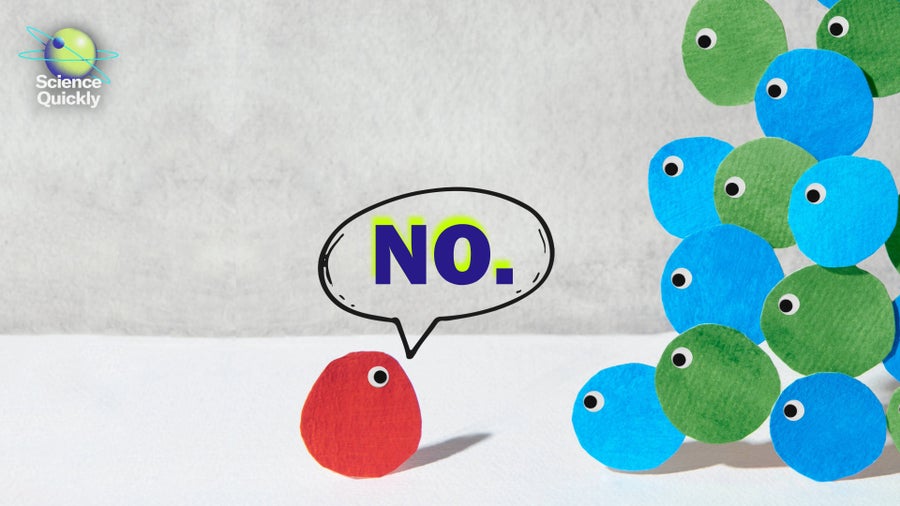

As children, many of us are taught that being “good” means being obedient: doing what we’re told by parents, teachers and authority figures. But that conditioning can make it incredibly difficult to speak up when we know something is wrong, whether that means correcting a mishandled coffee order or standing up against injustice. How can we learn to overcome these instincts when it really counts?

My guest today is Sunita Sah, a professor of management and organizations at Cornell University and the author of Defy: The Power of No in a World that Demands Yes. She thinks we could all stand to be a little more defiant, and she’s here to tell us why.

Thank you so much for coming on to chat with us today.

Sunita Sah: It’s wonderful to be here.

Feltman: So tell us a bit about your background. You know, what led you to studying defiance?

Sah: Ah, so this probably started way back in my childhood because as a child, I was really known for being an obedient daughter and student. And I remember asking my dad when I was quite young, “What does my name mean?” And he told me that Sunita means “good” in Sanskrit, and I mainly lived up to that: I was obedient at home. I was agreeable at school. I did all of my homework. I went to school on time. I even got my hair cut the way my parents wanted me to.

And these were the messages that I received, not just from parents but from teachers and the community: to be good. And what does that really mean? It means to do as you’re told, to obey, to be obedient, to be compliant. And I really internalized a lot of those messages, and I think they’re often messages that we give to children. You know, we like it when they’re obedient, and then we call that as being really good.

And I ended up studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh, which was really due to expectations. And while I was there, I did an intercalated degree in psychology, and I became fascinated by Stanley Milgram’s experiments on obedience to authority and why we go to the extent of that amount of compliance and obedience even when we’re causing harm, maybe even killing another person, with sort of dangerous electric shocks.

So that fascinated me, but I went back, and I finished my medical degree, and I worked as a junior doctor, and then I did some consulting work for the pharmaceutical industry. And during that time I became fascinated in how industry and the medical profession interact with each other, how they influence each other, how that affects physicians, and then how that trickles down to sort of decisions patients are making.

And I wanted to study all of this in more depth, and so I was doing an executive M.B.A. at London Business School, and I talked to a few professors there. They said if you wanna look at ethical dilemmas, I have to go to the U.S. So I traveled to the U.S., and I did a Ph.D. in organizational behavior, and that got me down the track of really being able to spend my time researching and studying this and teaching about why people take bad advice.

So at first I looked in medicine, then the finance industry got interested, then the criminal justice industry, and then basically, in all interpersonal interactions we have, I found this pattern of compliance everywhere.

Feltman: And for listeners who might need a little refresher, could you remind us what the Milgram experiments found?

Sah: So Stanley Milgram, he conducted his experiments in the early 1960s because he wanted to really investigate whether the Nazi refrain, “I was just following orders,” was a psychological reality or not. So he set up an experiment that basically was positioned as a learning or memory experiment, and whether people would learn better if they were—received some kind of punishment, which were electric shocks.

So we had people come in, and they met someone who was actually an actor, and they were told that this person would be the learner, and they would be strapped into something like—that looked like an electric chair that was gonna give them some electric shocks.

Then the participant was led to another room, and they were told that they were the teacher, and they were sat in front of a machine that had different levers on it, which were labeled with different voltages. And the lower voltages, it started at 15 volts, and it went up in 15-volt increments, all the way up to 450 volts, which was labeled “XXX.” And in advance, people, psychiatrists, predicted less than 1 percent would go up to 450 volts.

.

Tara Moore/Getty Images; Illustration composite by Scientific American

Tara Moore/Getty Images; Illustration composite by Scientific American

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article (sound on to listen:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment