Click the link below the picture

.

Alzheimer’s disease has proved to be a tricky target, and researchers and drug developers have been pursuing effective treatments for decades. Debates rage over the disorder’s underlying causes, and various approaches have faced one hurdle after another. But the field has reached a turning point. Over the past four years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved several therapies that address some of the condition’s potential biological roots rather than merely mitigating symptoms—a key scientific milestone. Despite the advances, however, there is still a long list of open questions and so much work to be done.

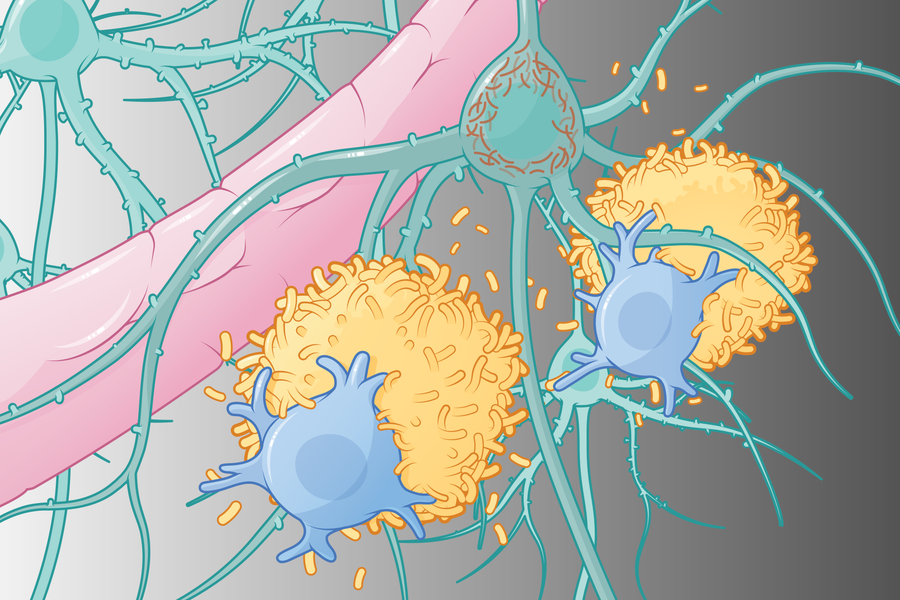

The brains of people who die with Alzheimer’s show a distinct biology: clumps or “plaques” of amyloid beta proteins in spaces between neurons and tangles of tau proteins that accumulate primarily within the nerve cells. One prevailing theory holds that amyloid builds up early, and tau tangles develop when nerve cell damage is underway, but cognitive symptoms are not yet apparent. Over time these pathogenic, or disease-causing, proteins disrupt nerve cell communication. The newest treatments—lecanemab and donanemab—bind to amyloid beta proteins, clear them from the brain, and modestly slow cognitive decline.

But the progression from disease-linked proteins to actual dementia is long and inexact, and amyloid and tau proteins accumulate in people with other neurodegenerative disorders, too. With Alzheimer’s, there is often a 20- to 30-year lag between the initial detection of amyloid and obvious cognitive decline. According to one study that predicted disease risk based on demographic data, death rates, and amyloid status, fewer than one quarter of cognitively healthy 75-year-old women who test positive for amyloid in a spinal fluid analysis or positron-emission tomography (PET) brain scan will develop Alzheimer’s dementia during their lifetime. Such findings suggest that amyloid alone is not driving disease progression and have spurred scientists to investigate other strategies.

DNA-sequencing analyses have identified gene variants that influence Alzheimer’s risk. Some of these genes point to a critical role of immune activity and inflammation in the disease process. Other research indicates that one way to reduce disease risk is through lifestyle changes. According to a 2024 report, nearly half of dementia cases worldwide could be prevented or delayed by actions addressing 14 modifiable risk factors, including hearing loss, physical inactivity, and vascular risk factors such as diabetes and smoking (many of which also impact immune activity and inflammation).

The Basics

A well-known hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease is the buildup of tau (a) and amyloid beta (b) proteins in the brain. Over time, plaques and tangles cause neuron damage (c) and cell death. But most Alzheimer’s patients have accumulated other proteins, too, such as alpha-synuclein, as well as blood vessel damage that can appear before amyloid plaques. Recent evidence suggests that inflammation, immune processes, and vascular risk factors also play a key role in the disease.

Treatment Targets

There are more than 100 ongoing clinical trials testing a variety of interventions, each of which targets one or more potential contributors to dementia. “We will get there in stages,” says Sudha Seshadri, a neurologist and founding director of the Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases at UT Health San Antonio in Texas. “The amyloid-lowering treatments are a piece of it. Immune-modulating drugs are probably going to be a piece of it,” she says. It will also be important to control for vascular risk, she adds, which “is important regardless of what else is happening.”

The mechanisms listed here are considered key elements of Alzheimer’s risk:

Neurotransmitter receptors • Proteins on nerve cell surfaces that receive signals and play a critical role in memory and learning. Some drugs for Alzheimer’s block harmful activity at these receptors, and others boost activity by preventing the breakdown of neurotransmitters.

Amyloid • A protein that, when misfolded, can build up outside of nerve cells in the brain and form plaques

that disrupt neural function. Several therapies aim to dissolve these deposits.

.

Now Medical Studios – Yea!

Now Medical Studios – Yea!

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment