Click the link below the picture

.

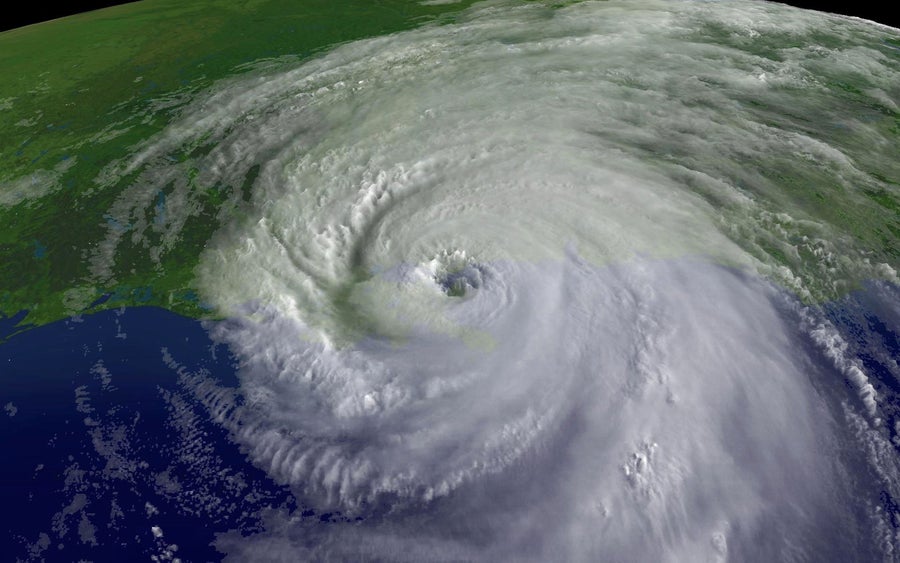

Like many other meteorologists around the U.S. Gulf Coast on the morning of August 26, 2005, Alan Gerard was monitoring the latest computer model forecasts for Hurricane Katrina, which had just emerged over the Gulf of Mexico after striking South Florida as a Category 1 storm. Gerard, then meteorologist in charge at the National Weather Service’s (NWS’s) office in Jackson, Miss., saw that the newest projections indicated that Katrina would track farther south than previous model runs had predicted. “It was a big change,” he says—and a concerning one because it meant that the storm would have more time over warm water to strengthen and that Katrina’s path had shifted westward, toward Mississippi.

With the weekend fast approaching and several hours before the official forecast would be updated, Gerard quickly e-mailed Mississippi’s emergency management agency to warn them that the state was facing a worse hit and that they needed to start preparing right away.

Just three days later, on August 29, Katrina rammed into the coast at the Louisiana-Mississippi border with a 20-mile-long wall of storm surge estimated at 24 to 28 feet high. (The exact heights that the surge reached aren’t known because most of the gauges, buildings, and other structures that would provide evidence of a high-water mark were obliterated.) In the subsequent hours, the levees around New Orleans failed, releasing torrents of water into the city and making Katrina the deadliest storm to hit the U.S. in nearly 80 years.

Despite the disaster that unfolded because of human mistakes, Katrina had been a well-predicted hurricane; the forecast errors involved were lower than the average at the time. But Katrina, along with the rest of the blockbuster 2004 and 2005 hurricane seasons, helped spark a dedicated, government-funded effort to make hurricane forecasts even better. Over the past 20 years, that project has nearly halved the error in predictions of where a storm will go and has given communities an extra 12 hours of warning time. By one estimate, these and other improvements have saved the nation up to $5 billion for each hurricane that hit the U.S. since 2007—3.5 times as much as the NWS’s budget for 2024. The resounding success is an example of “how this can all work when it’s done right,” Gerard says.

But that success, he and other hurricane experts warn, is under threat as the Trump administration is chopping away parts of the research staff and infrastructure that made such remarkable, lifesaving progress possible.

How Hurricane Forecasts Have Improved

When Frank Marks began forecasting hurricanes in the 1980s, it was only really possible to try to roughly predict the track that a storm would take. “Intensity was a wing and a prayer,” he says. Back then, a storm similar to Hurricane Erin, which parallelled the East Coast in mid-August 2025, would have likely prompted meteorologists to warn the entire coast of a possible hurricane hit because of the inherent uncertainty in forecasts. But this year, forecasters were able to tell that Erin would stay well out to sea; they only issued warnings for rip currents, heavy surf, and some storm surge in coastal areas. “To me, that is astounding, to see that evolution,” says Marks, who became director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Hurricane Research Division in 2002 and is now retired.

By the time Katrina formed near the Bahamas on Aug. 23, 2005, increased computing power, a better understanding of the physics of hurricanes, and more detailed observations of storms had substantially improved forecasts. But after the Gulf was battered by storms throughout 2004 and 2005, Vice Admiral Conrad Lautenbacher, then administrator of NOAA, thought there was still plenty of room for improvement, Marks says.“If you eliminate all of that research, you’re basically creating a stagnant weather service and a stagnant weather community in general.” —Alan Gerard, former National Weather Service meteorologistWhat grew out of that initial request was a fairly revolutionary effort that was eventually dubbed the Hurricane Forecast Improvement Project (HFIP). (The full name was subsequently changed to the Hurricane Forecast Improvement Program.) Its first step was to ask forecasters what problems they faced—and to bring together NOAA’s hurricane researchers and modelers, as well as academic scientists, to solve those issues.

.

In this satellite image from NOAA, a close-up of the center of Hurricane Katrina’s rotation is seen at 9:45 A.M. EST on August 29, 2005, over southeastern Louisiana. NOAA via Getty Images

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment