Click the link below the picture

.

People with type 1 diabetes must constantly rely on insulin injections or pumps, usually for the rest of their life after diagnosis. The autoimmune disease destroys the cells that produce the hormone, which is crucial to keeping blood sugar in check. But now research suggests a new therapy could finally allow people with type 1 diabetes to make insulin on their own.

A 42-year-old man who has lived most of his life with type 1 diabetes has become the first human to receive a transplant of genetically modified insulin-producing cells that can slip past the immune system’s mistaken attacks. This marks the first pancreatic cell transplant in a human to sidestep the need for immunosuppressant drugs—and it might even lead to a future cure for the disease, researchers say.

“This is the most exciting moment of my scientific career,” says cell biologist Per-Ola Carlsson of Uppsala University in Sweden, who helped develop the procedure. The new treatment, he says, “opens the future possibility of treating not only diabetes but other autoimmune diseases.”

Scientists injected nearly 80 million genetically tweaked cells into the participant’s forearm muscle, and 12 weeks later the cells were still alive and producing insulin. The recipient did require additional insulin injections—but the injected cells showed no signs of rejection, which the researchers say is a major step forward. The results were reported this month in the New England Journal of Medicine.

About two million people in the U.S. live with type 1 diabetes, which typically requires an intensive regimen of insulin injections and blood sugar monitoring. If their blood sugar runs amok, people face severe risks, including heart attacks, nerve damage, vision problems, kidney disease, and more.

For decades, scientists have struggled to develop therapies that can successfully replenish beta cells—the specialized insulin-producing cells that are found in the pancreas. Newly added functional beta cells are usually quickly destroyed because a type 1 diabetic immune system flags them as invaders. A few past attempts successfully transplanted donor islets—clusters of pancreatic cells that included beta cells—but these always ultimately triggered an aggressive immune response. And such a response requires recipients to take lifelong immunosuppressive drugs, which come with serious side effects, such as increased risks of infections and cancer. For example, at a conference in June, Boston-based Vertex Pharmaceuticals announced that 10 out of 12 participants who were treated with a stem-cell-based infusion during a clinical trial no longer required insulin injections a year after the therapy. But they may continue to need to immunosuppressants.

In the new study, Carlsson and his team looked for ways to dodge the immune response. First, they broke down a deceased donor’s pancreatic islets into single cells. Using the common gene-editing technique CRISPR, the researchers inactivated in some of these cells two genes that control the expression of proteins called human leukocyte antigens, which direct the immune system to the foreign cells. Without those markers, the immune system can’t easily recognize and destroy the donor cells.

To further evade immune system detection, the team made some cells express higher levels of a gene that discourages attacks by the body’s natural killer cells and macrophages, two types of immune cells. Three months after the treatment, although the immune system attacked some cells in the graft, it left the cells that had the inactivated genes and overexpressed gene alone. Blood tests showed no measurable immune cell activation or antibody production in response to these cells.

Before the transplant, the participant had no measurable naturally produced insulin and was receiving daily doses of the hormone. But within four to 12 weeks following the transplant, his levels rose slightly on their own after meals—showing that the new beta cells were releasing some insulin in response to glucose. Four adverse events occurred, but none were serious or related to the modified cells.

The advance “is amazing,” says Laura Alonso, chief of the division of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism at Weill Cornell Medicine, who was not involved in the new study. Unlike type 2 diabetes, in which people have poorly functioning beta cells, type 1 diabetes can destroy beta cells completely. Some people with type 1 diabetes may still have a small set of functional beta cells, but in more established cases, the immune system often whittles away all cells, Alonso says. For those established cases, she says, “cell-based therapy is where we need to go.”

.

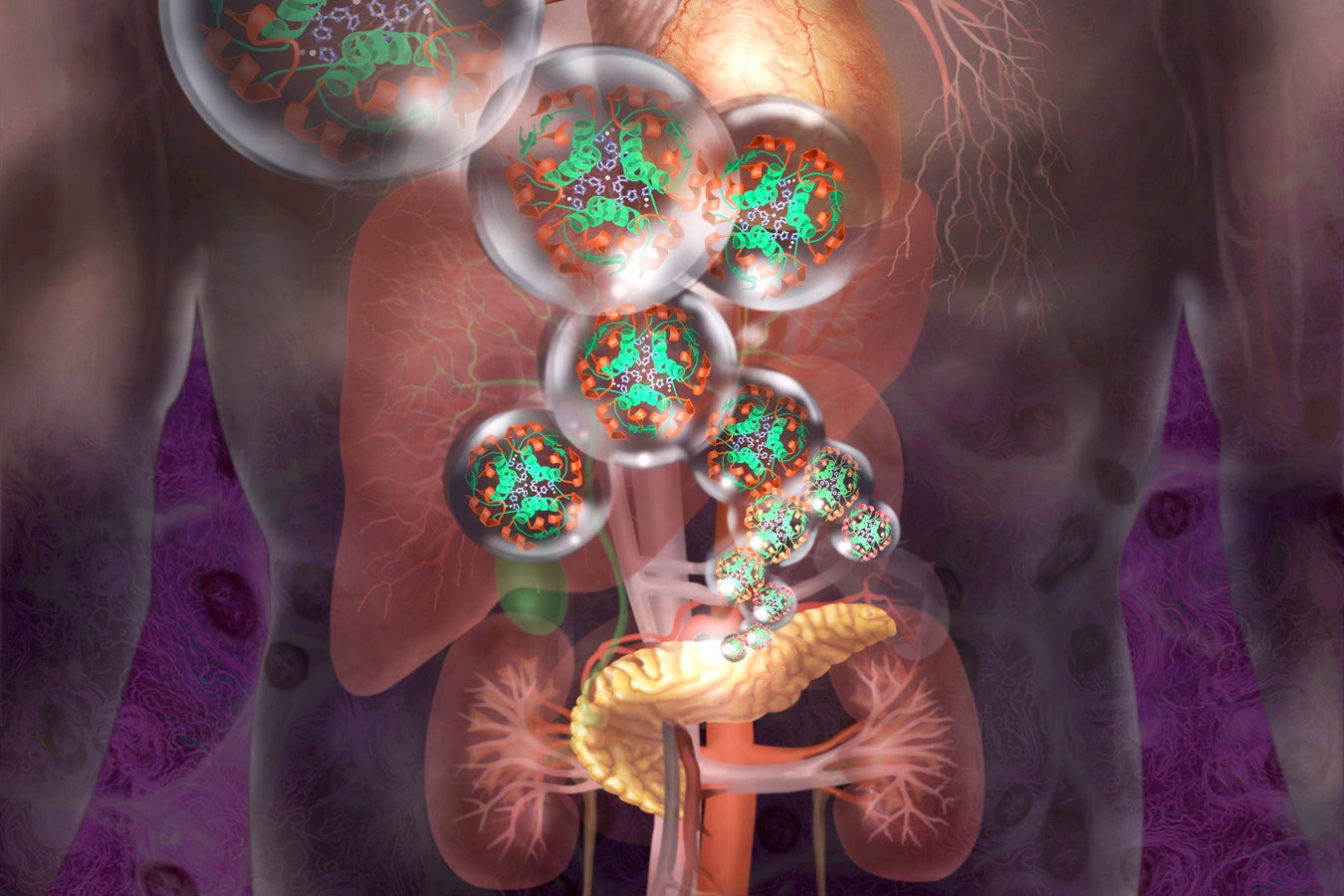

Insulin-producing cells can be genetically modified to hide from the immune system. Jim Dowdalls/Science Source

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment