Click the link below the picture

.

Aaron Lauda has been exploring an area of mathematics that most physicists have seen little use for, wondering if it might have practical applications. In a twist even he didn’t expect, it turns out that this kind of math could be the key to overcoming a long-standing obstacle in quantum computing—and maybe even for understanding the quantum world in a whole new way.

Quantum computers, which harness the peculiarities of quantum physics for gains in speed and computing ability over classical machines, may one day revolutionize technology. For now, though, that dream is out of reach. One reason is that qubits, the building blocks of quantum computers, are unstable and can easily be disturbed by environmental noise. In theory, a sturdier option exists: topological qubits spread information out over a wider area than regular qubits. Yet in practice, they’ve been difficult to realize. So far, the machines that do manage to use them aren’t universal, meaning they cannot do everything full-scale quantum computers can do. “It’s like trying to type a message on a keyboard with only half the keys,” Lauda says. “Our work fills in the missing keys.” He and his group at the University of Southern California published their findings in a new paper in the journal Nature Communications.

Lauda and his colleagues solve some of the problems with topological qubits by using a class of theoretical particles they call neglectons, named for how they were derived from overlooked theoretical math. These particles could open a new pathway toward experimentally realizing universal topological quantum computers.

Unlike ordinary qubits, which store information in the state of a single particle, topological qubits store it in the arrangement of several particles—which is a global property, not a local one, making them far more robust.

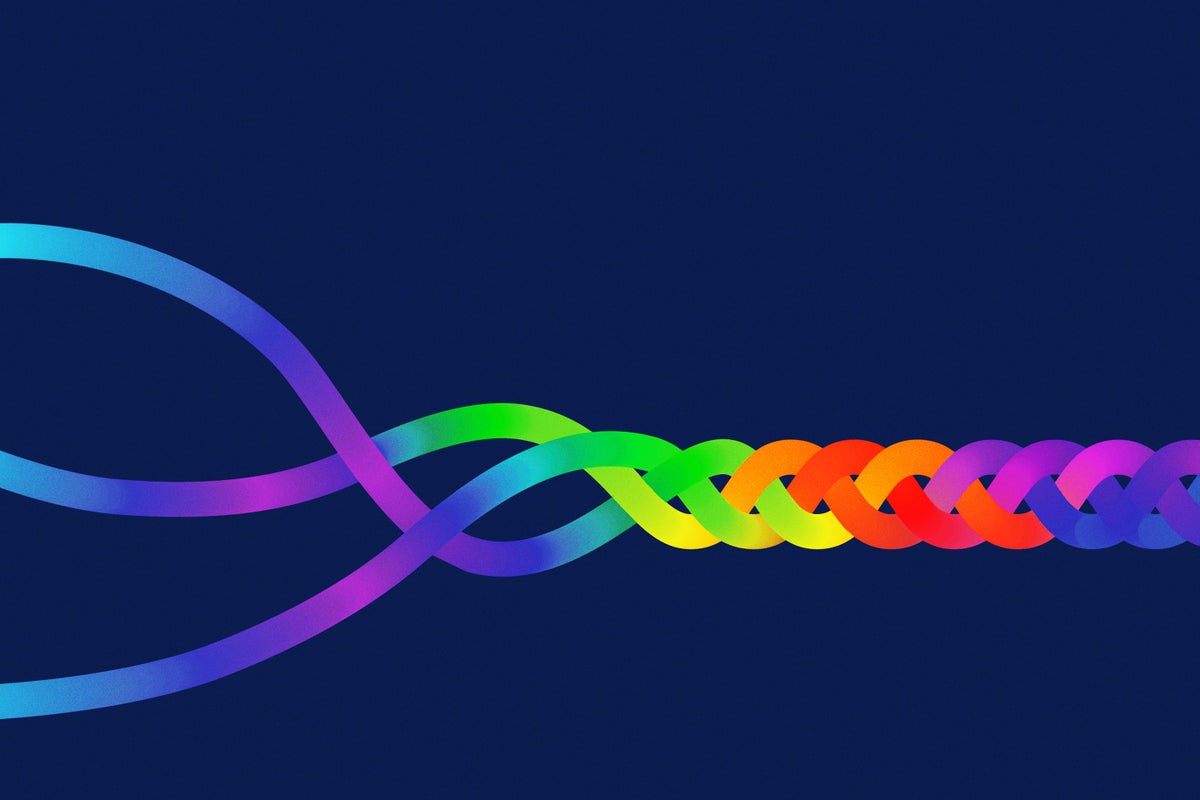

Take, for example, braided hair. The type and number of braids that a person has are global properties that remain the same regardless of how they shake their head. In contrast, the position of an individual hair strand is a local property that can shift with the slightest movement.

In our three-dimensional world, swapping two particles is like weaving one string over or under the other. You can always unweave them back to their original structure. When you swap particles in two dimensions, however, you cannot go over or under; you have to make the strings go through each other, which permanently changes the structure of the strings.

Because of this property, swapping two anyons can completely transform the state of a system. These swaps can be repeated among multiple anyons—a process called anyon braiding. The final state depends on the order in which the swaps, or braids, are formed, much like the way the pattern of a braid depends on the sequence of its strands.

Because braiding anyons changes the quantum state of the qubit, the procedure can be used as a quantum gate. Just as a logical gate in a regular computer changes bits from 0 to 1 to allow computation, quantum gates manipulate qubits. This braid-based logic is the foundation of how topological quantum computers compute.

Theoretically, many types of anyons exist. One variety, called Ising anyons, “are our best chance for quantum computing in real systems,” Lauda says. “However, by themselves, they are not universal for quantum computation.”

Picture a qubit as a number on a calculator display and the quantum gates as the buttons on the calculator. A nonuniversal computer is like a calculator that only has buttons for doubling or halving. You can reach plenty of numbers—but not all of them, which limits your computing power. A universal quantum computer would be able to reach all numbers.

.

Smartboy 10/Getty Images

Smartboy 10/Getty Images

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment