Click the link below the picture

.

In the spring of 2022, the U.S. space community selected its top priority for the nation’s next decade of science and exploration: a mission to Uranus, the gassy, bluish planet only seen up close during a brief spacecraft flyby in 1986. More than 2.6 billion kilometers from Earth at its nearest approach, Uranus still beckons with what it could reveal about the solar system’s early history—and the overwhelming numbers of Uranus-sized worlds that astronomers have spied around other stars. Now, President Donald Trump’s proposed cuts to NASA could push those discoveries further away than ever—not by directly canceling the mission but by abandoning the fuel needed to pull it off.

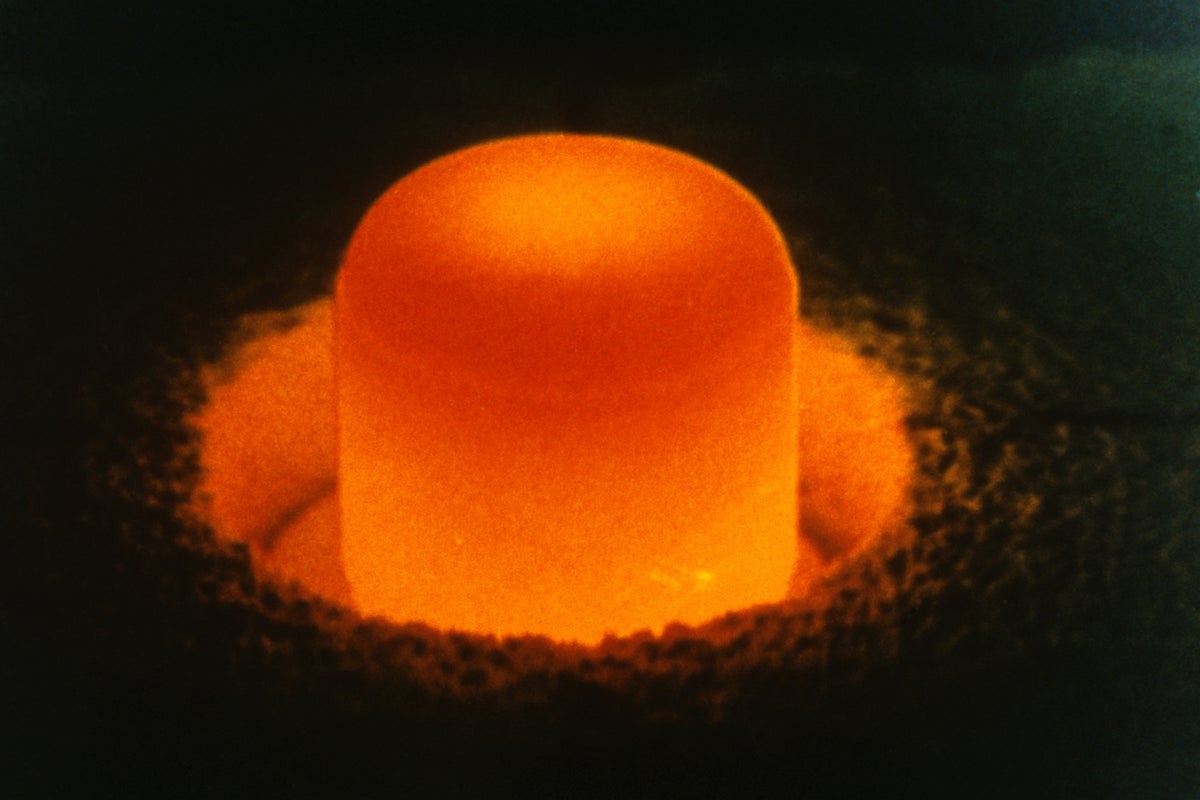

The technology in question, known as radioisotope power systems (RPS), is an often overlooked element of NASA’s budget that involves turning nuclear fuel into usable electricity. More like a battery than a full-scale reactor, RPS devices attach directly to spacecraft to power them into the deepest, darkest reaches of the solar system, where sunlight is too sparse to use. It’s a critical technology that has enabled two dozen NASA missions, from the iconic Voyagers 1 and 2 now traversing interstellar space to the Perseverance and Curiosity rovers presently operating on Mars.

But RPS is expensive, costing NASA about $175 million in 2024 alone. That’s largely because of the costs of sourcing and refining plutonium 238, the chemically toxic, vanishingly scarce, and difficult to work with radioactive material at the heart of all U.S. RPS. The Fiscal Year 2026 President’s Budget Request (PBR) released this spring suggests shutting down the program by 2029. That’s just long enough to use RPS tech on NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly

mission, a nuclear-powered dual-quadcopter drone to explore Saturn’s frigid moon Titan. After that, without RPS, no further U.S. missions to the outer solar system would be possible for the foreseeable future.

“It was an oversight,” says Amanda Hendrix, director of the Planetary Science Institute, who has led science efforts on RPS-enabled NASA missions such as Cassini at Saturn and Galileo at Jupiter. “It’s really like the left hand wasn’t talking to the right hand when the PBR was put together.”

Throughout its 400-odd pages, the PBR repeatedly acknowledges the importance of planning for the nation’s next generation of planetary science missions and even proposes funding NASA’s planetary science division better than any other part of the space agency’s science operations, which it seeks to cut by half. But “to achieve cost savings,” it states, 2028 should be the last year of funding for RPS, and “given budget constraints and the reduced pipeline of new planetary science missions,” the proposed budget provides no funding after 2026 for work by the Department of Energy (DOE) that supports RPS.

Indeed, NASA’s missions to the outer solar system are infrequent because of their long durations and the laborious engineering required for a spacecraft to withstand cold, inhospitable conditions so far from home. But what these missions lack in frequency, they make up for in discovery: some of the most tantalizing and potentially habitable environments beyond Earth are thought to exist there, in vast oceans of icy moons once thought to be wastelands. One such environment lurks on Saturn’s Enceladus, which was ranked as the nation’s second-highest priority after Uranus in the U.S.’s 2022 Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey.“The outer solar system is kind of the last frontier,” says Alex Hayes, a planetary scientist at Cornell University, who chaired the Decadal Survey panel that selected Enceladus. “You think you know how something works until you send a spacecraft there to explore it, and then you realize that you had no idea how it worked.”Unlike solar power systems—relatively “off-the-shelf” tech that can be used on a per-mission basis—RPS requires a continuous production pipeline that’s vulnerable to disruption. NASA’s program operates through the DOE, with the space agency purchasing DOE services to source, purify, and encapsulate the plutonium 238 fuel, as well as to assemble and test the resulting RPS devices. The most common kind of RPS, a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, converts the thermal energy released from plutonium 238’s natural decay to as much as 110 watts of electrical power. Any excess heat helps keep the spacecraft and its instruments warm enough to function.

Establishing the RPS pipeline took around three decades, and the program’s roots lie in the bygone Cold War era of heavy U.S. investment in nuclear technology and infrastructure. Preparing the radioactive fuel alone takes the work of multiple DOE facilities scattered across the country: Oak Ridge National Laboratory produces the plutonium oxide, then Los Alamos National Laboratory forms it into usable pellets, which are finally stockpiled at Idaho National Laboratory. Funding cuts would throw this pipeline into disarray and cause an exodus of experienced workers, Hendrix says. Restoring that expertise and capability, she adds, would require billions of dollars and a few decades more.

.

A pellet of plutonium 238, illuminated by the glow of its own radioactivity. NASA and other space agencies use this material in radioisotope power sources for interplanetary missions to the solar system’s darkest, most distant destinations. Photo Researchers/Science Source

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment