Click the link below the picture

.

Astronomers have found nearly 6,000 exoplanets orbiting other stars. But for every confirmed detection, there are countless mere hints, inconclusive observations that could just as well be blips of cosmic noise or glitches in a telescope. Most are too tenuous to take seriously, but every so often, one of these candidate planets is so tantalizing and potentially transformative that it can’t be ignore.

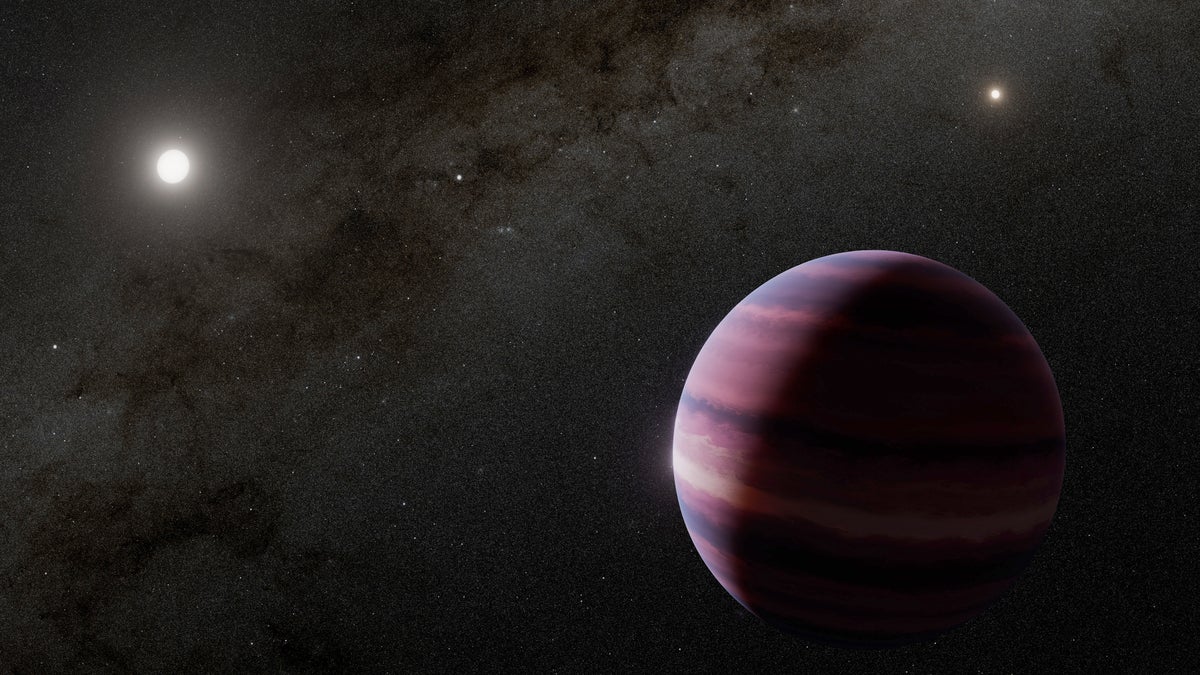

That’s certainly the case for one recently spotted by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) around a sunlike star called Alpha Centauri A, part of the nearest star system to Earth. If the finding were confirmed to represent a planet—and not instead a clump of dust or some instrumental aberration—it would be a gas giant, akin to a warmer version of our own Saturn. It would orbit within Alpha Centauri A’s habitable zone, the starlight-bathed region where liquid water can persist on a planet’s surface. But the world itself would likely be lifeless, smothered beneath thick layers of gas. Any accompanying moons, however, could have better chances for harboring oceans—and perhaps even life.

Announced on August 7 and described in two preprint papers that have been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, the candidate and its possibilities call to mind worlds from science fiction, such as the jungle moon of Pandora in James Cameron’s Avatar films—which, incidentally, orbits a gas giant called Polyphemos around, yes, Alpha Centauri A. But there’s still a chance that the real-world JWST discovery will prove to be a mirage.

“If it’s real, it’s amazing,” says Elisabeth Matthews, an exoplanet-focused astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “It’s a really exciting candidate—quite an intriguing candidate,” she says. “The authors work hard to make a case for why this, frankly, small and faint blob of light is believable, but I think there are still some open questions that need to be answered to really be 100 percent sure.”

The finding has been nearly a decade in the making, says Charles Beichman, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology and a co-author of the two new papers. In 2017, nearly half a decade before JWST would launch, he sent an e-mail to scientists positing that the telescope’s giant 6.5-meter mirror, paired with its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), might be able to see planets orbiting Alpha Centauri A. “When you stop laughing, let’s think about doing this project,” Beichman told them.

It was a bold suggestion, particularly when JWST was still on the ground, he admits. The telescope “was never really meant to look at a star that’s this bright, moving this fast and located, as Alpha Centauri is, right in the middle of the galactic plane, where there’s thousands of stars,” Beichman says.

Despite those obstacles, the appeal was irresistible. Alpha Centauri A is about the same size and age as our sun. And the star and its two companions, the slightly smaller Alpha Centauri B and the tiny red dwarf star Proxima Centauri, comprise the nearest stellar system to our own—just about four and a half light-years away. Because the Alpha Centauri system is spitting distance from us, astronomically speaking, it’s a bright, perennially popular target for scientists who may not be able to conduct similar observations on dimmer, more distant stars.

This is especially true for direct imaging, the technical term for when astronomers actually manage to take an exoplanet’s picture. Most exoplanetary discoveries instead arise through far more indirect means, such as the dip in a star’s light caused by a world passing between its sun and our telescope or the tiny wobbling of a star caused by an orbiting planet’s gravitational tug. Only in rare cases can astronomers truly see an alien world; typically, a planet needs to be very big and bright—as well as rather far from its sun—to offer any hope for astronomers to glimpse it against the overwhelming glare of its star.

But because Alpha Centauri A is cosmically close, Beichman and his colleagues thought that they could use JWST’s stunning power to accomplish the feat even for a planet that orbits relatively close to the star, within just a few times the distance between Earth and our sun. “Alpha Centauri just lets us cheat because it’s closer than everybody else,” Beichman says.

Although proximity makes for easier studies, this is counterbalanced against the system’s vexing complexity. Alpha Centauri A is the brightest star of the three in the system, but its stellar companion Alpha Centauri B is still quite bright—and quite close, crowding into telescopes’ field of view. Although JWST is equipped with a coronagraph—a masking tool to block out the glare from one star—it can’t do much to curtail this second, planet-obscuring source of light.

For Aniket Sanghi, a Ph.D. student in astrophysics at Caltech and a co-author of the two new papers, that difficulty only made the task more alluring. “I was looking for the next challenging object to work on, and Alpha Centauri A turned out to be one of the most challenging objects,” Sanghi says.

Faced with the brightness of not one but two stars overpowering JWST’s exoplanet-hunting optics, the researchers turned to a surprising strategy: enlisting yet another star. They found a particularly nondescript star that they could use as a stand-in. By observing this other star centered on and blocked by the coronagraph and then off-center and unmasked, the researchers were able to model how its light flowed through JWST’s optics. This created a template by which Alpha Centauri B’s light could then be subtracted out from the precious images of Alpha Centauri A.

And when the researchers tackled the feat in August 2024, they found exactly what they hoped for: a faint blob of light nestled near the blocked-out Alpha Centauri A. “As a direct imager, you’re always confounded by artifacts,” Sanghi says. “You’re very skeptical of anything you see. But this one just popped out so clearly.”

Sanghi and his colleagues tried to undermine their own data, striving to explain how the blob could be stray light within JWST’s optics or a background object in the sky, but nothing quite stuck.

.

This artist’s concept shows what a gas giant orbiting Alpha Centauri A could look like. NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, R. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC)

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment