Click the link below the picture

.

Every four years, soccer fans eagerly await the sport’s biggest event: the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) World Cup. But before each dramatic kickoff, artists and researchers spend years designing, testing, and revising the official match ball. Recently, images of the planned ball for the 2026 competition were leaked, and its design incorporates math, physics, and style in some surprising ways.

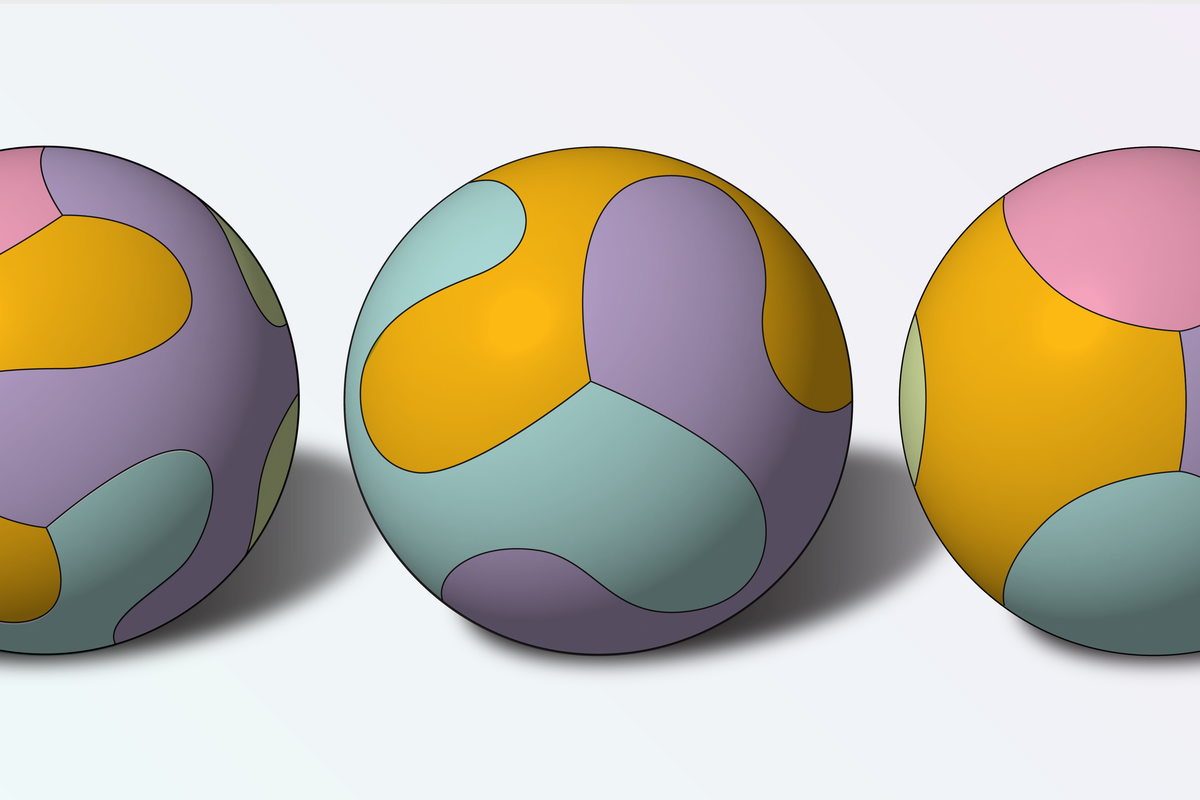

Called the Trionda (Spanish for “triwave”), the new ball celebrates the three host nations—the U.S., Mexico, and Canada—for the first multinational-hosted World Cup. The ball is stitched together from just four panels, the smallest number yet for a FIFA World Cup ball. And it represents a significant reduction from the 20-paneled Al Rhila ball that was used in 2022.

The design of any soccer ball hinges on an age-old question: How can one make rounded shapes out of flat material? Every FIFA World Cup ball so far has borrowed inspiration from some of math’s simplest three-dimensional shapes: the platonic solids. These five shapes are the only convex polyhedrons built from copies of a single regular polygon where the same number of faces meet at each corner.

The icosahedron, which has 20 triangle faces and a relatively ball-like appearance, seems promising, but it’s still a bit too pointy to roll around. If we cut off (or truncate) the points of an icosahedron, each of the triangles becomes a hexagon, and each of the points becomes a pentagon.

This is the shape of the classic soccer ball, originally called the Telstar ball and used in the official FIFA World Cup match in 1970. The stark black-and-white color scheme was meant to increase visibility on black-and-white TVs, which were still prevalent at the time.

The Trionda ball is also based on a platonic solid—the tetrahedron—which at first seems the least ball-like of all the famous shapes. A tetrahedron is made of four triangles, three of which meet at every point. The trick in the Trionda design is in the shape of the panels. Though they have three points like a typical triangle, the panels’ edges are curves that fit together to give the ball a more rounded exterior.

This method of making a pointy platonic solid rounder by curving the edges of the faces may be familiar to soccer fans; in fact, the design of the Trionda ball strongly evokes the Brazuca, a six-paneled ball based on a cube that starred in the 2014 World Cup.

Basing the Trionda ball on a tetrahedron might be a risky choice; the last match ball based on that shape was highly controversial. The Jabulani ball, whose name means “rejoice” in Zulu, might have been a bit too joyful. Players complained it was unpredictable in the air and didn’t react the way they expected it to. The design of the Jabulani combined both methods of turning a platonic solid into a sphere: cutting off the corners to make eight faces and turning the edges of the faces into curves. It also had a unique feature, shared with none of the official match balls before or since: three-dimensional, spherically molded panels.

The Jabulani may have been the roundest ball yet. So why didn’t it work as intended? The answer has to do with “drag”—the force of air particles pushing back on the ball as it flies through space. Typically, the faster a ball moves, the more drag it experiences, which can slow it down and change its trajectory. But each ball also has a “critical speed” past which the drag on the ball decreases significantly. The smoother a ball is, the higher the critical speed barrier becomes. This is why the surfaces of golf balls have dimples: they lower the critical speed and help the balls move faster through the air. These effects mean that rounder and smoother isn’t always better—and may explain the Jabulani’s unpredictable behavior.

.

Each World Cup brings an exciting new ball design. The 2026 Trionda ball is at center. Amanda Montañez

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment