Click the link below the picture

.

Keiko Ogura was just 8 years old when the atoms in the Hiroshima bomb started splitting. When we met in January, some 300 feet from where the bomb struck, Ogura was 87. She stands about five feet tall in heels, and although she has slowed down some in her old age, she moves confidently, in tiny, shuffling steps. She twice waved away my offered arm as we walked the uneven surfaces of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, first neutrally and then with some irritation.

Ogura can still remember that terrible morning in August, 80 years ago. Her older brother, who later died of cancer from radiation, was on a hilltop north of the city when the Enola Gay made its approach. He saw it shining small and silver in the clear blue sky.

Ogura was playing on a road near her house; her father had kept her home from school. “He had a sense of foreboding,” she told me. She remembers the intensity of the bomb’s white flash, the “demon light,” in the words of one survivor. The shock wave that followed had the force of a typhoon, Ogura said. It threw her to the ground, and she lost consciousness—for how long, she still doesn’t know.

Like many people who felt the bomb’s power that day, Ogura assumed that it must have been dropped directly on top of her. In fact, she was a mile and a half away from the explosion’s center. Tens of thousands of people were closer. The great waves of heat and infrared light that roared outward killed hundreds of Ogura’s classmates immediately. More than 20,000 children were killed by the bomb.

Ogura told me that after the initial explosion, fires had raged through the city for many hours. Survivors compared the flame-filled streets to medieval Buddhist scroll paintings of hell. When Ogura awoke on the road, the smoke overhead was so thick that she thought night had fallen. She stumbled back to her house and found it half-destroyed, but still standing. People with skin peeling off their bodies were limping toward her from the city center. Ogura’s family well was still functional, and so she began handing out glasses of water. Two people died while drinking it, right in front of her. A black rain began to fall. Each of its droplets was shot through with radiation, having traveled down through the mushroom cloud’s remnants. It stained Ogura’s skin charcoal gray.

In the days following the bombing, Ogura’s father cremated hundreds of people at a nearby park. The city itself seemed to have disappeared, she said. In aerial shots, downtown Hiroshima’s grid was reduced to a pale outline. More than 60,000 structures had been destroyed. One of the few that remained upright was a domed building made of stone. It still stands today, not far from where Ogura and I met. The government has reinforced its skeletal structure, in a bid to preserve it forever. Circling the building, I could see in through the bomb-blasted walls, to piles of rubble inside.

Ogura and I walked to a monumental arch at the center of the Peace Memorial Park, where a stone chest holds a register of every person who is known to have been killed by the Hiroshima bomb. To date, it contains more than 340,000 names. Only a portion of them died in the blast’s immediate aftermath. Tens of thousands of others perished from radiation sickness in the following months, or from rare cancers years later. Every generation alive at the time was affected, even the newest: Babies who were still in their mothers’ wombs when the bomb hit developed microcephaly. For decades, whenever one of Ogura’s relatives took ill, she worried that a radiation-related disease had finally come for them, and often, one had.

.

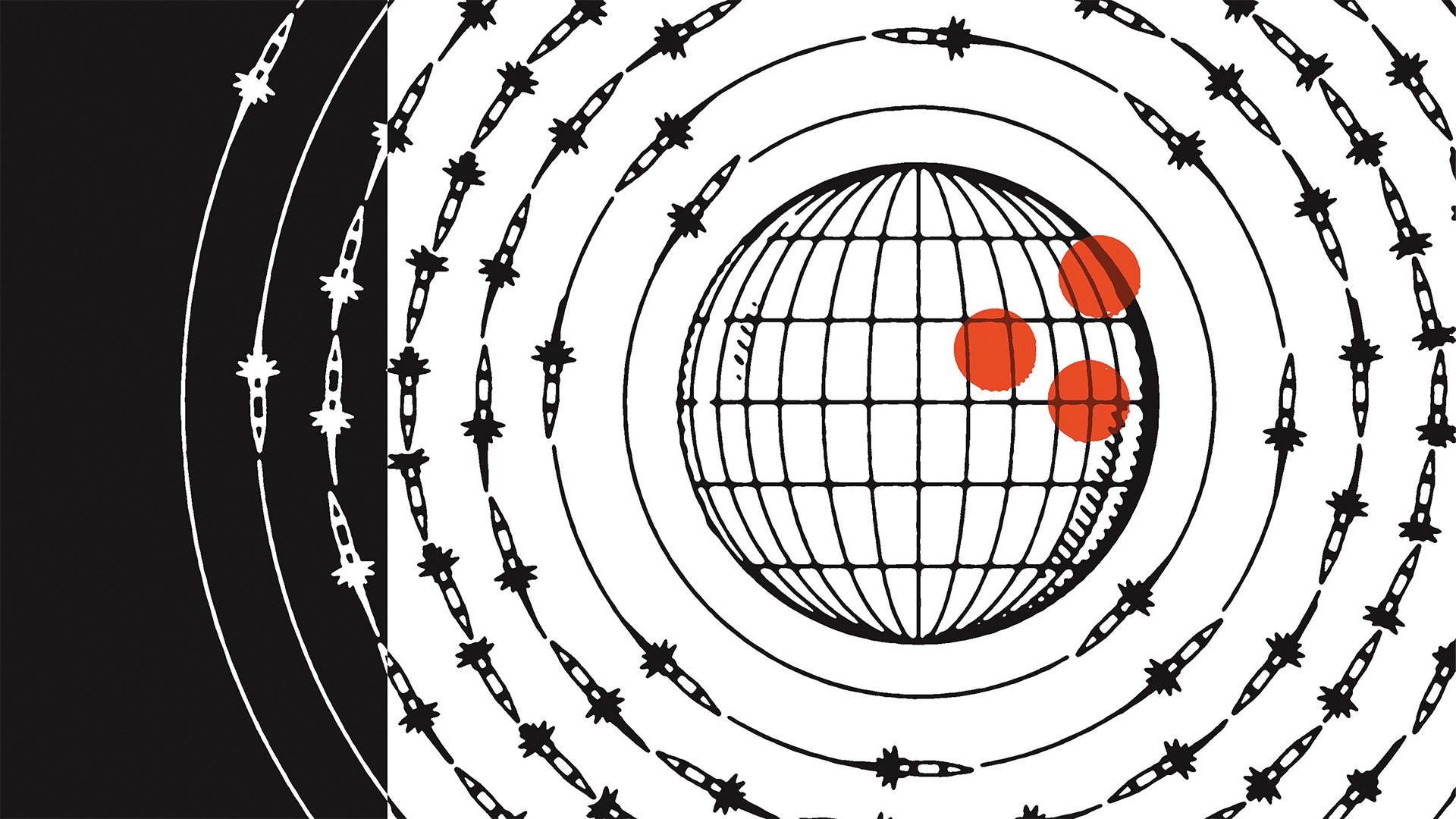

Nuclear club

Nuclear club

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment