Click the link below the picture

.

Most people have never heard of vacuum decay, but if it happened, it would be the biggest natural disaster in the universe. Sure, an asteroid could destroy a city or wipe out life on Earth. A supernova could fry the ozone layer. If a blast of energy from a spinning black hole hit our planet, it could rip apart the entire solar system. As dramatic as these disasters are, they’d still leave behind rocks, gas, and dust. With time that matter could come together again, making new stars and planets and maybe life.

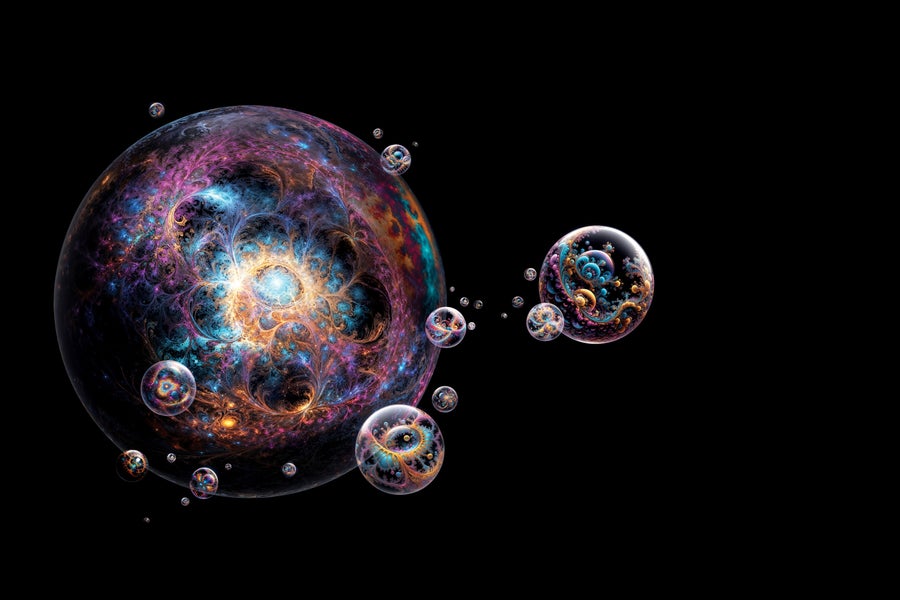

Vacuum decay is different. This cataclysm would result from a change in the Higgs field, a quantum field that pervades all of space. It would be triggered by pure chance, creating a bubble that would expand at almost the speed of light, transforming all in its path. Inside that bubble, the laws of physics we take for granted would change, making matter as we know it (and, consequently, life) impossible.

According to physicists’ current best estimates, vacuum decay is extremely unlikely, with an almost unthinkably small chance of its taking place close enough to our part of the universe to affect us. Still, the chance isn’t zero, and some recent estimates suggest the likelihood might be slightly less minuscule than we used to think. Ultimately, though, the possibility of an apocalyptic quantum bubble shouldn’t cause anyone to lose any sleep.

Even so, scientists have been studying how and why this scenario might play out. The answers to these questions don’t just reveal some fascinating aspects of the quantum world—they may also turn the questions on their heads: rather than making us worry about the threat a vacuum bubble poses, the fact that the universe has survived this long without one may teach us something about the deepest unsolved problems in physics.

All the objects we’re used to—every animal, vegetable, and mineral—are made up of atoms, and those atoms are made up of ripples in quantum fields. Each field is like a setting on a kind of universal control panel. If you could jiggle the electron switch on the control panel, you’d see an electron pop into existence. Most of these switches have a default value of zero: electrons aren’t likely to be in most places, for example. These defaults are sticky—it takes effort, in the form of energy, to push a switch out of its default position. How much energy it requires is determined by Albert Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2, which defines the relation between energy and mass: the more massive a particle, the stickier the default for the switch of its field.

Inside the bubble the laws of physics we take for granted would change.

You might think that in truly empty space, all these switches are set to zero. That’s true for most quantum fields, but some have a different default. One such case is a quantum field proposed by several physicists in 1964, including British physicist Peter Higgs, for whom it was later named. Try to set the Higgs field to zero, and it will resist. The universe “wants” to have a certain amount of Higgsness in it, a default called a vacuum expectation value. It is this amount of Higgs field, instead of zero, that one finds in the vacuum of empty space.

Pushing the Higgs field from this default setting is quite difficult. Scientists finally accomplished it in 2012, when an experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva managed to measure the tiniest, briefest possible shift in the Higgs field. Just as jiggling the electron switch makes an electron, jiggling the Higgs switch makes a particle called a Higgs boson. These particles swiftly vanish after we create them, with the Higgs switch rushing back to its default while knocking other, easier-to-shift switches around, creating particles such as electrons or photons instead. But LHC scientists managed to create enough Higgs bosons to definitively detect them and prove the Higgs field exists.

The Higgs field is special because it controls the mass of all other particles. In effect, it serves as a kind of master switch, determining how sticky all the other switches’ defaults are. If you could grab the Higgs switch and drag it toward zero, you’d find that all the other switches became much easier to flick. In other words, a lower Higgs value would mean it took less energy to make an electron or a quark.

Physicists think of the task of moving the Higgs field from its default value as being a bit like rolling a boulder up a hill. If the boulder rests at the bottom of a valley, you can try to push it upward, but if you let it go, it will just roll down again.

.

Mondolithic Studios

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment