Click the link below the picture

.

I always wanted to understand life. What moves us? What allows us to heal and thrive? And what goes wrong when we get sick or when we eventually stop breathing and die? My search for answers to these stupendously ambitious questions led me, it now seems inexorably, to mitochondria.

In biology classes from high school through university, I learned that mitochondria are little objects that reside within each cell and serve as “powerhouses,” combining oxygen and food to yield energy for the body. This idea of mitochondria being little batteries with a built-in charger, about as interesting as the one in my phone, left me unprepared for the vital reality of these organelles when I first saw them under a microscope in 2011. They were luminous because of a glowing dye I had put in them, and they were dynamic—constantly moving, stretching, morphing, touching one another. They were beautiful. That night, a graduate student alone in a dark laboratory in Newcastle upon Tyne in England, I became a mitochondriac: hooked on mitochondria.

A profound insight by biologist Lynn Margulis helped me make some sense of what I was seeing. She postulated in 1967 that mitochondria descend from a bacterium that was engulfed by a larger ancestral cell about 1.5 billion years ago. Instead of consuming this tidbit, the larger cell let it continue living within. Margulis called this event endosymbiosis, which means, roughly, “living or working together from the inside.” The host cell had no energy source that used oxygen, which, thanks to plants, was already abundant in the atmosphere; mitochondria filled this gap. The unlikely union allowed cells to communicate and cooperate and let their awareness expand beyond their own boundaries, enabling a more complex future in the form of multicellular animals. Mitochondria made cells social, binding them in a contract whereby the survival of each cell depends on every other one, and thus made us possible.

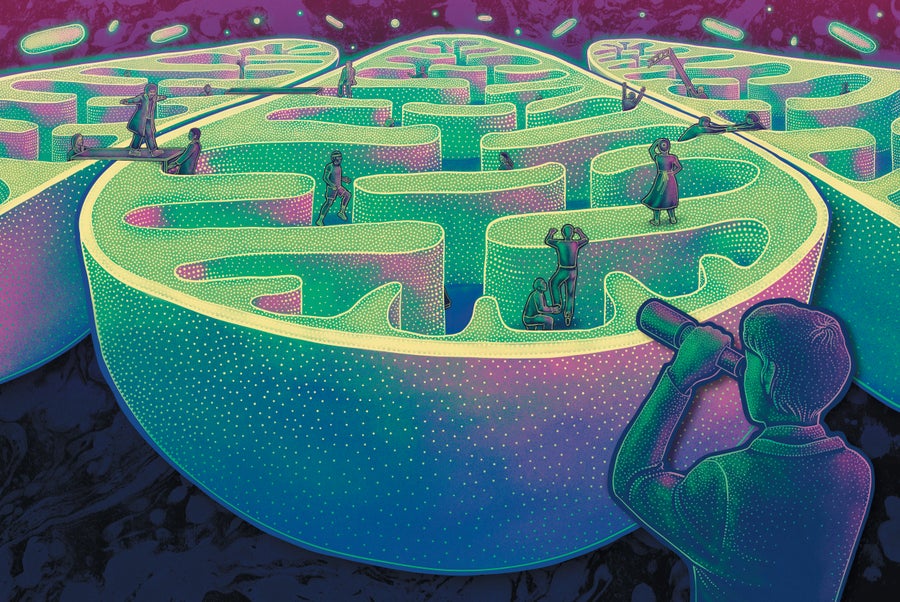

Amazingly, my co-workers and I have discovered that mitochondria are themselves social beings. At least, they foreshadow sociality. Like the bacterium they descended from, they have a life cycle: old ones die out, and new ones are born out of existing ones. Communities of these organelles live within each cell, usually clustered around the nucleus. Mitochondria communicate, both within their own cells and among other cells, reaching out to support one another in times of need and generally helping the community flourish. They produce the heat that keeps our bodies warm. They receive signals about aspects of the environment in which we live, such as air pollution levels and stress triggers, and then integrate this information and emit signals such as molecules that regulate processes within the cell and, indeed, throughout the body.

When our mitochondria thrive, so do we. When they malfunction—when, for instance, their ability to change energy into forms required for biochemical reactions is impaired—we may experience conditions as diverse as diabetes, cancer, autism, and neurodegenerative disorders. And as mitochondria accumulate defects over a lifetime of stress and other insults, they contribute to aging and, ultimately, death. To understand these processes—to see how to sustain physical and mental health—it helps to understand how energy moves through our bodies and minds. That requires a deeper look into mitochondria and their social lives.

Long before I got my first glimpse of mitochondria, I had boned up on the basics of their structure and biology. We inherit our mitochondria from our mother—from the egg cell, to be precise. Mitochondria have their own DNA, which consists of only 37 genes, compared with the thousands of genes in the spiraling chromosomes inside the cell nucleus. This ring of mitochondrial DNA, or mtDNA, is sheltered within two membranes. The outer shell, shaped like the skin of a sausage, encases the mitochondrion and selectively allows molecules to enter or exit. The inner membrane is made of densely packed proteins and has many folds, called cristae, which serve as a site for chemical reactions, much like the plates suspended inside a battery.

Rather than being like battery chargers, mitochondria are more like the motherboard of the cell.

In the 1960s, British biochemists Peter Mitchell and Jennifer Moyle discovered how electrons derived from carbon in food combine with oxygen in the cristae, releasing a spark of energy that is captured as a gradient in electrical voltage across the membrane. This voltage provides the driving force for all processes in the body and brain, from warming to manufacturing molecules to thinking. Mitochondria also produce a molecule called adenosine triphosphate, which serves as a portable unit of energy that powers hundreds of biochemical reactions within each cell.

.

Jennifer N.R. Smith

Jennifer N.R. Smith

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment