Click the link below the picture

.

Ah, it’s a lovely night for enjoying the outdoors. You go outside in the warm summer air to listen to the crickets and breathe in the scents of verdant life, and then turn your head to the heavens. You see hundreds of stars in the sky, and the brightest are conspicuously twinkling and gleaming.

Some are even shifting their colors across the rainbow, delighting your eyes and mind—unless you’re out there to do some observing with a telescope. That twinkling is lovely for any average stargazer to behold, but scientifically, it’s a pain in the astronomer.

Twinkling is the apparent rapid variation of brightness and color of the stars. It’s technically called scintillation, from the Latin for “sparkle,” which is apt. While it is admittedly lovely, it’s still the bane of astronomers across the world.

For millennia, twinkling was misunderstood. As with so many scientific principles, it was misdiagnosed by ancient Greeks such as Aristotle, who attributed it to human vision. At that time, he and his peers believed that the eye actively created vision by sending out beams that illuminated objects and allowed us to see them. But these beams were imperfect, so the belief went, and the farther away an object was, the more the beam would be distorted; stars, being very far away, suffered this flaw greatly, causing them to twinkle. It was Isaac Newton, through his studies of optics, who finally determined the true cause.

A fundamental property of light—true of all waves, in fact—is that it bends when it goes from one medium to another. You’re familiar with this: a spoon sitting in a glass of water looks bent at the top of the liquid. This is called refraction, and in the case of the spoon, it happens when the light goes from the water in the glass to the air on its way to your eye, distorting the shape of the otherwise unbent spoon. The amount of refraction depends on the properties of the materials through which the light travels. Density, for instance, can dictate the degree of refraction for light moving through gas—so light traveling through air alone will still bend if the air has different densities from one spot to the next.

If Earth’s atmosphere were perfectly static and homogeneous, then the refraction of starlight would be minimal. Our air is always in motion, however, and far from smooth. Winds far above the planet’s surface stir the air, creating turbulence. This roils the gases, creating small air packets of different densities that move to and fro.

Starlight passing through one such parcel of air will bend slightly. From our point of view on Earth, the position of the star will shift slightly when that happens. The air is also in motion, so from moment to moment, the starlight will pass through different parcels on its way to your eye or your detector, shifting position each time, usually randomly because of the air’s turbulent motion. What you see on the ground, then, is the star rapidly shifting left, right, up and down, and all directions in between, several times per second—in other words, twinkling.

The amount of the shift is confusingly called “seeing” by astronomers, and it’s actually quite small. It’s usually only a few arcseconds, a very small angle on the sky—the full moon, for example, is about 1,800 arcseconds wide. Stars, though, are so far away from us that they appear to be a minuscule fraction of an arcsecond wide, a tiny point of light to the eye, so even this minuscule arcsecond-scale shifting makes them appear to dance around.

.

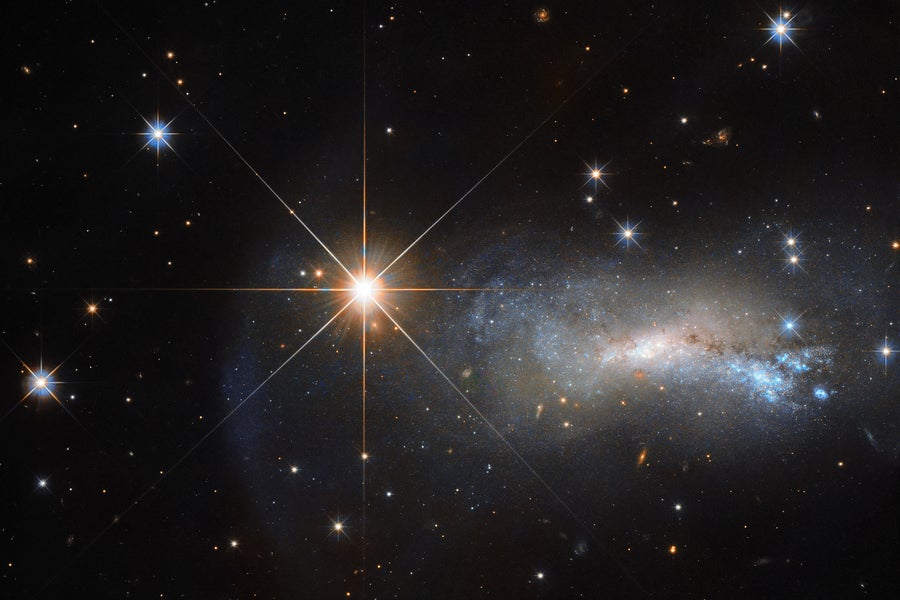

ESA/Hubble/NASA (CC BY 4.0)

ESA/Hubble/NASA (CC BY 4.0)

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment