Click the link below the picture

.

Inside a laboratory nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, amid a labyrinth of lenses, mirrors, and other optical machinery bolted to a vibration-resistant table, an apparatus resembling a chimney pipe rises toward the ceiling. On a recent visit, the silvery pipe held a cloud of thousands of supercooled cesium atoms launched upward by lasers and then left to float back down. With each cycle, a maser—like a laser that produces microwaves—hit the atoms to send their outer electrons jumping to a different energy state.

The machine, called a cesium fountain clock, was in the middle of a two-week measurement run at a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) research facility in Boulder, Colo., repeatedly fountaining atoms. Detectors inside measured photons released by the atoms as they settled back down to their original states. Atoms make such transitions by absorbing a specific amount of energy and then emitting it in the form of a specific frequency of light, meaning the light’s waves always reach their peak amplitude at a regular, dependable cadence. This cadence provides a natural temporal reference that scientists can pinpoint with extraordinary precision.

By repeating the fountain process hundreds of thousands of times, the instrument narrows in on the exact transition frequency of the cesium atoms. Although it’s technically a clock, the cesium fountain could not tell you the hour. “This instrument does not keep track of time,” says Vladislav Gerginov, a senior research associate at NIST and the keeper of this clock. “It’s a frequency reference—a tuning fork.” By tuning a beam of light to match this resonance frequency, metrologists can “realize time,” as they phrase it, counting the oscillations of the light wave.

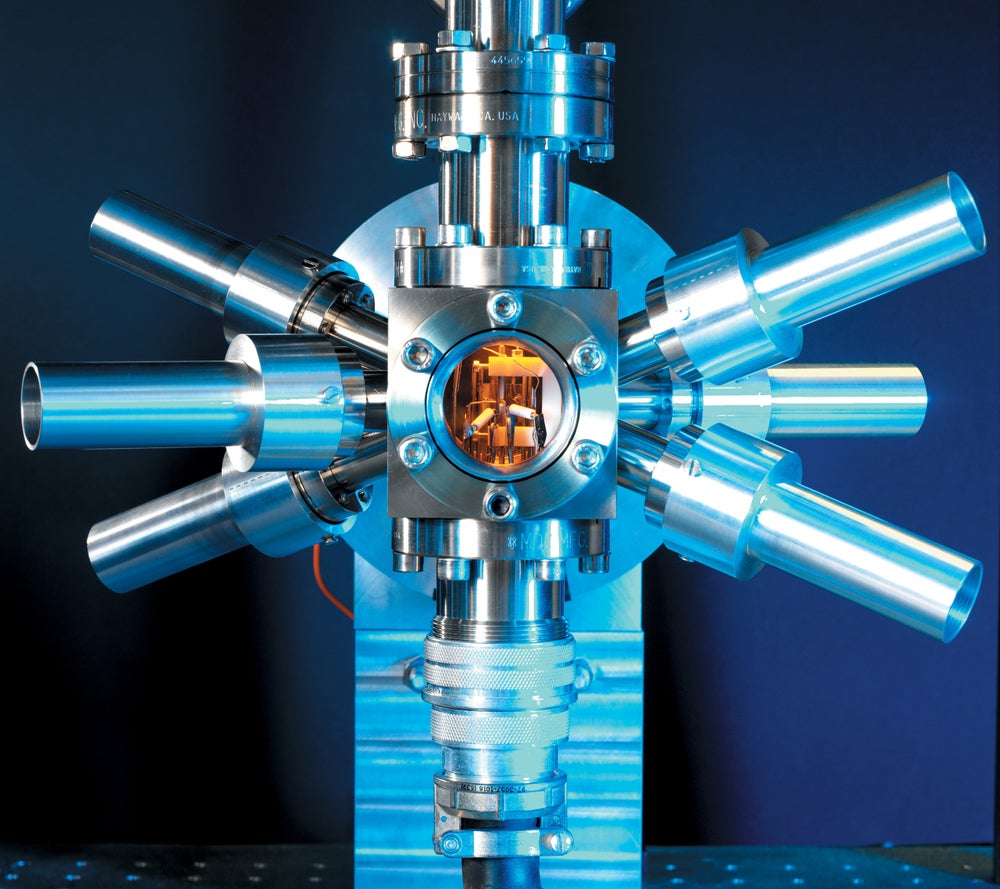

The signal from this tuning fork—about nine gigahertz—is used to calibrate about 18 smaller atomic clocks at NIST that run 24 hours a day. Housed in egg incubators to control the temperature and humidity, these clocks maintain the official time for the U.S., which is compared with similar measurements in other countries to set Coordinated Universal Time, or UTC.Gerginov, dressed casually in a short-sleeve plaid shirt and sneakers, spoke of the instrument with an air of pride. He had recently replaced the clock’s microwave cavity, a copper passageway in the middle of the pipe where the atoms interact with the maser. The instrument would soon be christened NIST-F4, the new principal reference clock for the U.S. “It’s going to be the primary standard of frequency,” Gerginov says, looking up at the metallic fountain, a three-foot-tall vacuum chamber with four layers of nickel-iron-alloy magnetic shielding. “Until the definition of the second changes.”

Since 1967 the second has been defined as the duration of 9,192,631,770 cycles of cesium’s resonance frequency. In other words, when the outer electron of a cesium atom falls to the lower state and releases light, the amount of time it takes to emit 9,192,631,770 cycles of the light wave defines one second. “You can think of an atom as a pendulum,” says NIST research fellow John Kitching. “We cause the atoms to oscillate at their natural resonance frequency. Every atom of cesium is the same, and the frequencies don’t change. They’re determined by fundamental constants. And that’s why atomic clocks are the best way of keeping time right now.”

But cesium clocks are no longer the most accurate clocks available. In the past five years, the world’s most advanced atomic clocks have reached a critical milestone by taking measurements that are more than two orders of magnitude more accurate than those of the best cesium clocks. These newer instruments, called optical clocks, use different atoms, such as strontium or ytterbium, that transition at much higher frequencies. They release optical light, as opposed to the microwave light given out by cesium, effectively dividing the second into about 50,000 times as many “ticks” as a cesium clock can measure.

.

A strontium optical clock produces about 50,000 times more oscillations per second than a cesium clock, the basis for the current definition of a second. Andrew Brookes/National Physical Laboratory/Science Source

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment