Click the link below the picture

.

I was born with nystagmus, a neurological condition that affects my vision, and until I was in my 30s, I’d only met one person that shared it. At a holiday party with my parents when I was probably 8 or 9, my mom pointed out a boy across the room. “He has nystagmus like you,” she said. “But not exactly. Your eyes bop all over your head and his just move back and forth. He also has albinism, which is why his eyes do that. We don’t know what causes yours.” I regarded the ice blond teen across the room. I don’t think we spoke. What would I have said to him? My vision was a point of shame and something I tried to hide. If kids pointed it out, I usually ended up in tears.

My son inherited my nystagmus. It’s given me the unusual opportunity to watch how people react to his vision as a window into how the world reacts to me. Being able to watch my child closely — the flickering of his eyes as he nursed, the tilt of his head as he searched for me among the waiting moms (yes, they were always all moms) at school pickup, as he struggled to read the routes on the approaching buses just like I did — these were moments of familiarity but also of novelty, as I observed how the world observed him. The social stigma of appearing disabled trained out of me many of the behaviors that mark him as “different,” movement patterns that I have no personal recollection of, but can pick up from the family photos in which I always was tilting my head, my eyes struggling like his do to make contact with the aperture of the lens.

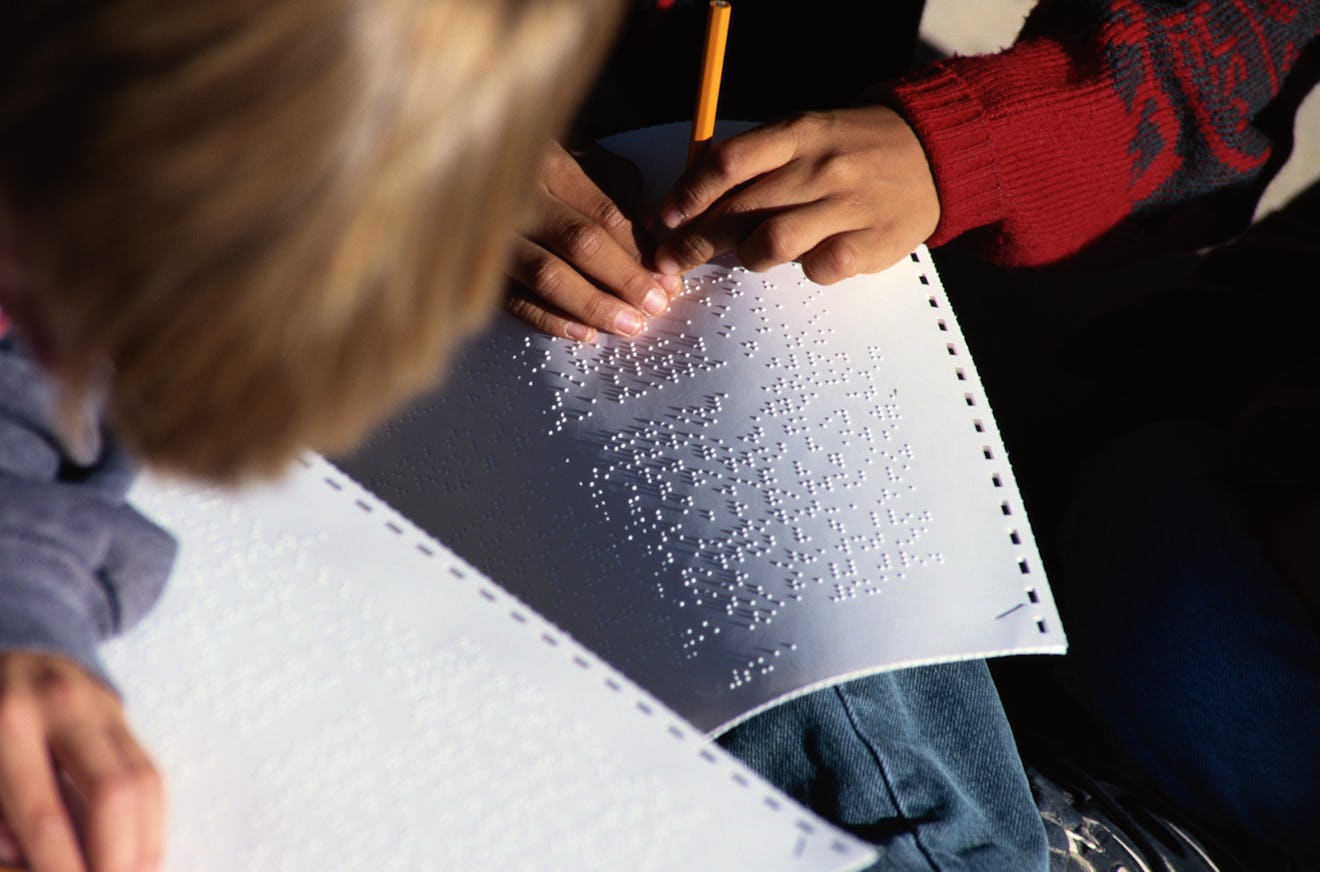

In some ways, it has given me the opportunity to revisit my own childhood experience of disability. And one of my main regrets, if I have any, is that I never learned braille. According to the National Federation of the Blind, only about 10% of blind and low-vision children in the U.S. are learning braille. Much of this is due to our bias toward learning through sight, and so children who have any vision are pushed toward text magnification as a replacement. But like me, every person I’ve asked who is blind or low-vision wishes they’d been taught braille as a child or, if they’d been introduced to it, wish they’d been pushed to gain true fluency. Access to language is power. That’s why I’m determined to make sure my kid learns it.

In middle school, I learned to hate public speaking. I was in every sense an “overachiever,” so I remember preparing fastidiously for my first presentation in English class, where we had to present instructions about how to perform a skill or task for our classmates. I had rainbow pastel index cards where I’d written my presentation talking points.

Then I got my grade. It wasn’t perfect. I’d been marked down because I held the note cards in front of my face and I’d failed to make eye contact with my classmates. It wasn’t so much the grade that bothered me, but the awareness that when I spoke publicly, my disability was super visible. In my attempt to assimilate and be “normal,” I feared that visibility more than anything else. From that point on, any kind of speaking in front of other people made me extremely nervous. I dreaded when other people had to watch me talk and avoided it as much as I could.

There are moments where my throat catches as I watch my kid encountering situations l can remember from my own childhood.

It wasn’t until my mid-30s when I started to work with other disabled people and from their comfort with themselves and speaking publicly, I pushed myself to get through my shame. But even with this new confidence, public speaking is still a struggle for me. The more stressed I get, the more my eyes move and so I stumble over words and easily lose my place.

To compensate, I stopped using written notes for my presentations. Instead of reading from my book at author’s events, I used slides with images to prompt me through the outline of my presentation.

Then I watched as a blind advocate read a proclamation at a public hearing using braille. Her presentation was flawless — the kind of flawlessness I’d been dreaming of since my stumbles in middle school. I wanted that skill. But braille, like any language, is difficult to learn in adulthood. If I worked really hard at it, maybe someday I’d be able to read it fluently enough to crib notes for a talk, but I’d never have the speed of someone who learned it as a child.

In the 1820s, braille was created by and embraced by students at the National Institute for the Blind in Paris. But soon their sighted educators tried to stop its adoption, at one point burning all the braille books. These educators preferred a language that they too had access to, like raised letter shapes embossed on the page. Braille was harder for sighted educators to read and it threatened their control and their careers.

.

Scott T. Baxter/Photodisc/Getty Images

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment