Click the link below the picture

.

Ever since humans started gazing at the heavens through telescopes, we have discovered, bit by bit, that in celestial terms we’re apparently not so special. Earth was not the center of the universe, it turned out. It wasn’t even the center of the solar system! The solar system, unfortunately, wasn’t the center of the universe either. In fact, there were many star systems fundamentally like it, together making up a galaxy. And, wouldn’t you know, the galaxy wasn’t special but one of many, which all had their own solar systems, which also had planets, some of which presumably host their own ensemble of egoistic creatures with an overinflated sense of cosmic importance.

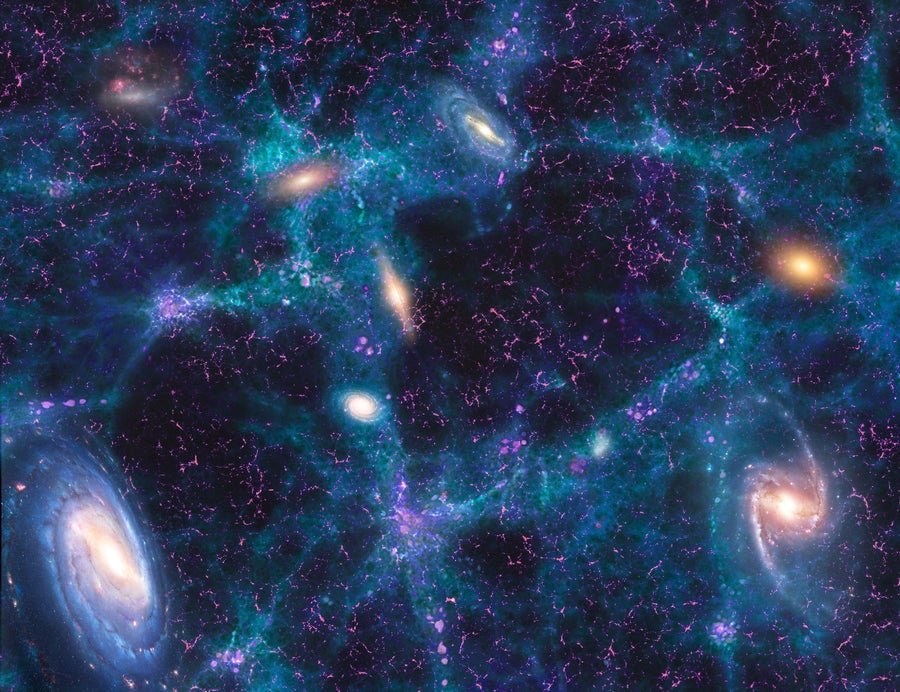

This notion of mediocrity has been baked into cosmology, in the form of the “cosmological principle.” Its gist is that the universe is basically the same everywhere we look—homogenized like milk, made of common materials evenly distributed in every direction. At the top of the cosmic hierarchy, giant groups of galaxies clump into sprawling, matter-rich filaments and sheets around gaping intergalactic voids, but past that, structure seems to peter out. If you could zoom way out and look at the universe’s big picture, says Alexia Lopez of the University of Central Lancashire in England, “it would look really smooth.”

Lopez compares the cosmos with a beach: If you plunked a handful of sand under a microscope, the sand grains would look like the special individuals they are. “You would see the different colors, shapes, and sizes,” she says. “But if you were to walk across the beach, looking out at the sand dunes, all you would see is a uniform golden beige color.”

That means Earth (or any of the other trillions of planets that must exist) and its tiny corner of the cosmos appear to hold no particularly privileged place in comparison to everything else. And this homogeneity is convenient for astronomers because it lets them look at the universe in part as a reliable way of making inferences about the whole; whether here in the Milky Way or in a nameless galaxy billions of light-years distant, prevailing conditions should be essentially the same.

This simplifying ethos applies to everything from understanding how dark matter weighs down galaxy clusters to estimating how common life-friendly conditions might be throughout the cosmos, and it allows astronomers to simplify their mathematical models of the universe’s past as well as their predictions of its future. “Everything is based on the idea that [the cosmological principle] is true,” Lopez says. “It is also a very vague assumption. So it’s really hard to validate.”

Validation is especially challenging when significant evidence exists to the contrary—and a host of recent observations suggest indeed that the universe could be stranger and have larger variations than cosmologists had so comfortably supposed.

If that’s the case, humans (and anyone else out there) actually might have a sort of special view of the light-years beyond—not privileged, per se, but also not average, in that “average” would no longer even be a useful concept at sufficiently large scales. “Different observers may see slightly different universes,” at least at large scales, says Valerio Marra, a professor at the Federal University of Espírito Santo in Brazil and a researcher at the Astronomical Observatory of Trieste in Italy.

Astronomers haven’t thrown out the cosmological principle just yet, but they are gathering clues about its potential weaknesses. One approach involves looking for structures so large they challenge cosmic smoothness even at a hugely wide zoom. Scientists have calculated that anything wider than about 1.2 billion light-years would upset the homogeneous cosmic apple cart.

.

An illustration of the cosmic web, the universe’s large-scale structure of composed of galaxy-rich clumps and filaments alongside giant intergalactic voids mostly bereft of matter. At even larger scales, cosmic structure seems to smooth out into near-featureless homogeneity. Mark Garlick/Science Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment