Click the link below the picture

.

Most astronomers would love to find a planet, but Mike Brown may be the only one proud of having killed one. Thanks to his research, Pluto, the solar system’s ninth planet, was removed from the pantheon—and the public cried foul. How can you revise our childhoods? How can you mess around with our planetariums?

About 10 years ago Brown’s daughter—then around 10 years old—suggested one way he could seek redemption: go find another planet. “When she said that, I kind of laughed,” Brown says. “In my head, I was like, ‘That’s never happening.’”

Yet Brown may now be on the brink of fulfilling his daughter’s wish. Evidence he and others have gathered over the past decade suggests something strange is happening in the outer solar system: distant subplanetary objects are being found on orbits that look sculpted, arranged by an unseen gravitational force. According to Brown, that force is coming from a ninth planet—one bigger than Earth but smaller than Neptune.

Nobody has found Planet Nine yet. If it’s really out there, it’s too far and too faint for almost any existing telescope to spot it. But that’s about to change. A new telescope, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, is about to open its mechanical eyes. When it does, it should catch millions of previously undetected celestial phenomena, from distant supernovae to near-Earth asteroids—and, crucially, tens of thousands of new objects around and beyond Pluto.

If Brown’s hidden world is real, Rubin will almost certainly find it or strong indirect evidence that it exists. “In the first year or two, we’re going to answer that question,” says Megan Schwamb, a planetary astronomer at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland—and, just maybe, the solar system will once again have a ninth planet.

Pluto was discovered in 1930 and always seemed to be a lonely planet on the fringes of the solar system. But in the early 2000s skywatchers found out that Pluto had company: other rime-coated worlds much like it were popping up in surveys of that benighted frontier. And in 2005, using California’s Palomar Observatory, Brown—an astronomer at the California Institute of Technology—and two of his colleagues spied a far-flung orb that would change the way we perceive the solar system.

That orb was Eris. It was remarkably distant—68 times as far from the sun as Earth. But at roughly 1,500 miles in diameter, it was just a little larger than Pluto. “The day I found Eris and did the calculation about how big it might be, I was like, ‘Okay, that’s it. Game’s up,’” Brown says. Either Eris was going to become a new planet, or Pluto wasn’t what we thought.

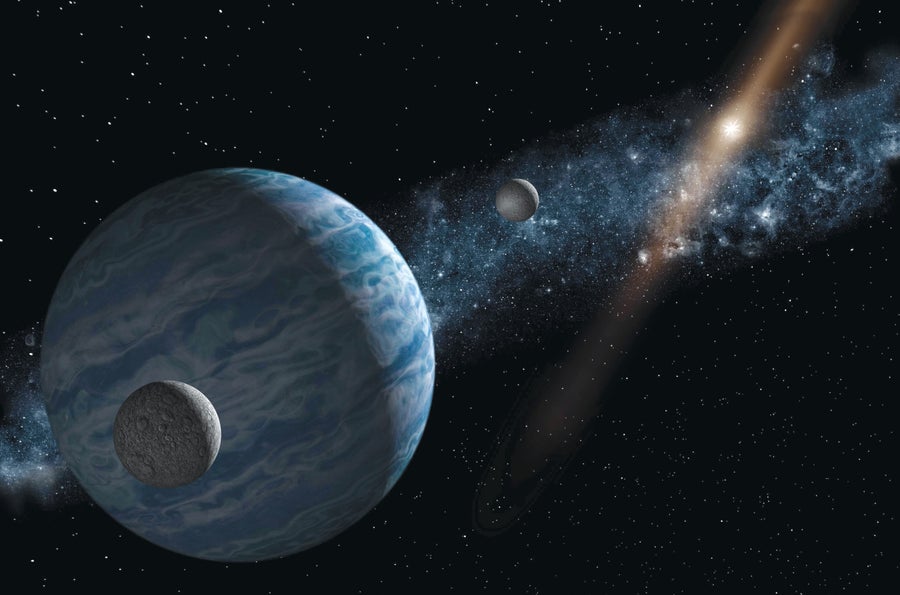

Finding a ninth planet would be huge. Such a discovery could change what we know about our solar system’s past.

In 2006 officials at the International Astronomical Union decided that to qualify as a planet, a body must orbit a star, must be sufficiently massive for gravity to squish it into a sphere, and must have a clear orbit. Pluto, which shares its orbital neighborhood with a fleet of other, more modest objects, failed to overcome the third hurdle. Pluto became a “dwarf planet”—but its demotion didn’t make it, or its fellow distant companions, any less beguiling to astronomers.

.

Ron Miller

Ron Miller

.

.

Click the link below for the complete article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment