Click the link below the picture

.

How few corners can a shape have and still tile the plane?” mathematician Gábor Domokos asked me over pizza. His deceptively simple question was about the geometry of tilings, also called tessellations—arrangements of shapes, called tiles or cells, that fill a surface with no gaps or overlaps. Humans have a preoccupation with tessellation that dates back at least to ancient Sumer, where tilings featured prominently in architecture and art. But in all the centuries that thinkers have tinkered with tiles, no one seems to have seriously pondered whether there’s some limit to how few vertices—sharp corners where lines meet—the tiles of a tessellation can have. Until Domokos. Chasing tiles with ever fewer corners eventually led him and his small team to discover an entirely new type of shape.

It was the summer of 2023 when Domokos and I sat at a wood picnic table at the Black Dog, a cozy spot for pizza and wine just a few blocks from the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, where Domokos is a professor. He reached across the table to grab a paper pizza menu and flip it over, revealing a blank underside, and gestured to me to grab a pen. The midsummer sky was taking on shades of orange and indigo as I filled the menu with triangles. Domokos watched expectantly. “You’re allowed to use curves,” he finally said. I started filling the page with circles, which of course can’t fill space on their own. But Domokos lit up. “Oh, that’s interesting!” he said. “Keep going, you can mix shapes. Just try to keep the average number of corners as low as possible.”

I kept going. My page of circles filled with increasingly desperate, squiggly forms. Domokos’s pizza Margherita had long since disappeared, but he wasn’t quite ready to leave. A quick glance at my crude drawing wasn’t enough to determine its average number of corners, let alone the minimum possible. But the right answer must have been something less than the triangle’s three—otherwise, the question would be boring.

That observation seemed to satisfy the mathematician, who revealed that the real answer is two. “That’s an easy question,” he said. “But what about 3D?”

“This is a tool that can reasonably describe, at least to me, a wide range of more physically relevant things than just polyhedrons stuck together.” —Chaim Goodman-Strauss, mathematician

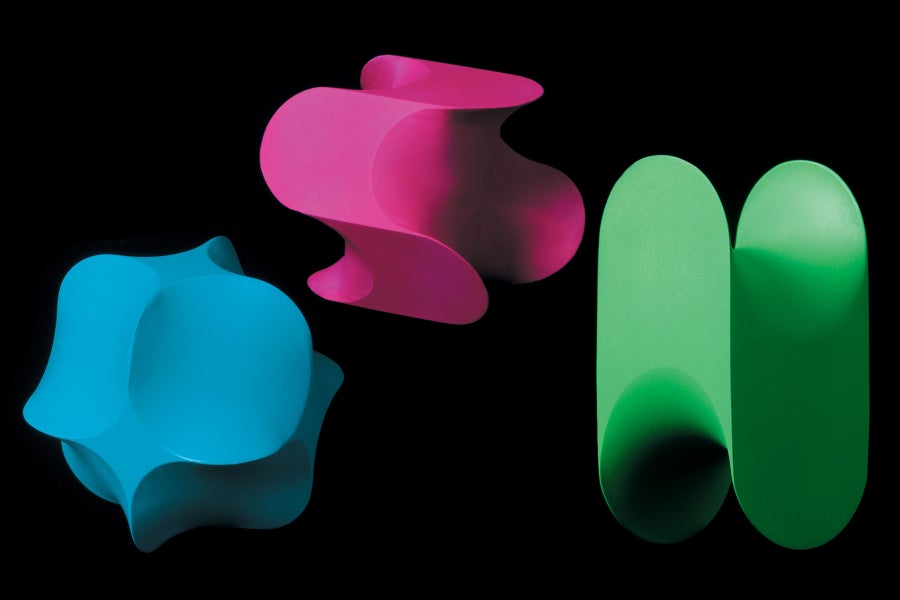

Now, more than a year after that evening at the pizza shop, Domokos has the answer. Finding it was an exciting, frustrating challenge that ultimately led him and three colleagues to discover “soft cells,” shapes that can fit together to completely fill a flat surface or a three-dimensional space with as few corners as possible. In two dimensions, soft cells have two corners bridged by curves. But in 3D, these curvy, almost organic forms have no corners at all. Once the researchers identified the new shapes, they began to see them all over the place—in nature, art and architecture. The results have now been published in the journal PNAS Nexus.

Although soft cells hadn’t been categorized by mathematicians before—no one had noticed or named them in an academic paper—they abound in art and nature, from the architecture of Zaha Hadid, “Queen of the Curve,” to the forms of zebra stripes. Krisztina Regős, Domokos’s graduate student, found the first natural 3D soft cell tucked away in the chambers of the nautilus shell, an object that’s become iconic for showcasing the convergence of math and biology. “They were in front of our eyes the whole time,” Regős says. This connection to such a famous shape led Domokos to fear that his group would be scooped. He swore his collaborators to secrecy until their discovery was ready to be published. (It came out in September.) At the end of his lesson over pizza, he even took the paper menu, folded it up and pocketed it. Just to be safe.

In retrospect, it should have been obvious that soft cells exist, says mathematician Joseph O’Rourke of Smith College, who wasn’t involved in the study. But to think to ask such a question, “to even imagine that you can tile space with no vertices,” he says, is original. “I found that quite surprising and very clever.”

.

Photographs of 3D-printed shapes show soft cells derived from space filling polyhedra. Blue is derived from a truncated octahedron, pink is from a hexagonal prism and green is from a cube. Jelle Wagenaar

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment