Click the link below the picture

.

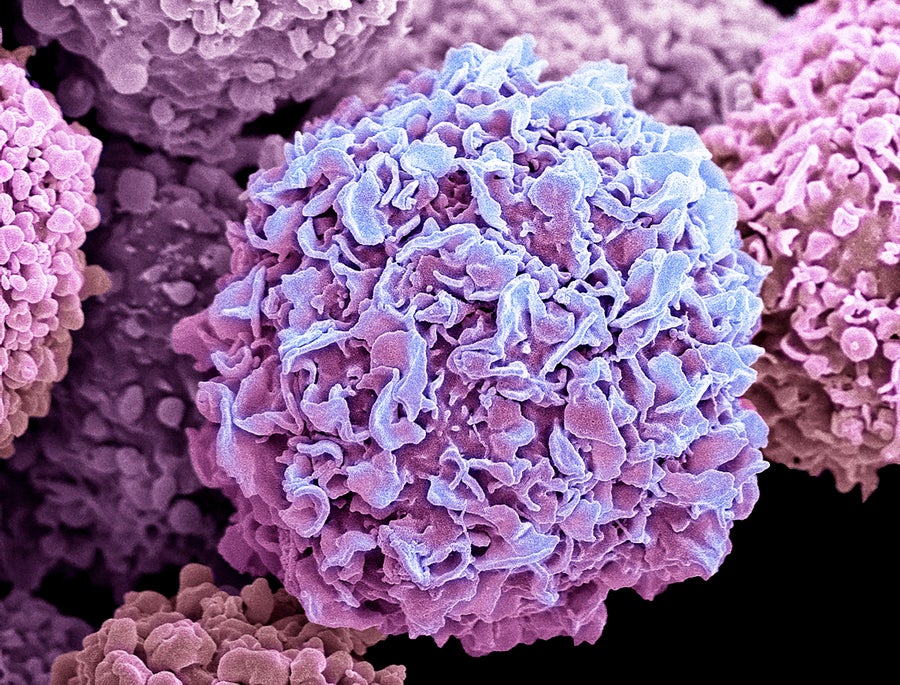

In the age of precision medicine, targeted drugs are transforming cancer treatment. But cancer cells persist in many patients, even in breast cancer, where much-lauded hormone therapies and targeted therapies have had a huge impact. Despite these and other advances in precision medicine, the five-year survival rate for advanced breast cancer is still only about 30 percent.

To help more patients whose breast cancer recurs, scientists have developed targeted therapies, which typically rely on monoclonal antibodies or small-molecule inhibitors to stop runaway cell growth. A new type of therapy takes a different approach. Unlike prior generations of small-molecule drugs, a new class of compounds called protein degraders not only bind to cancer-driving target proteins—they spur cells to digest them.

This two-pronged attack hits an essential signaling pathway that drives many breast cancers that are more resistant to standard treatments. The goal for this tactic is to be as specific as possible, in order to leave more healthy cells unharmed. This advance is unleashing opportunities for therapeutic approaches that might “prolong life with fewer treatment side effects,” says Katherine Ansley, a clinical associate professor of hematology and oncology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

An elusive target

Discovered in the mid-1980s, PI3K is an intracellular enzyme, part of an essential pathway that signals healthy cells to grow and proliferate. Several isoforms of PI3K exist, each with distinct and essential roles. Mutations in one of them, known as PI3K-alpha, result in overactive growth signaling in as many as 40 percent of women with the most common form of breast cancer—tumors that grow in response to the hormones estrogen or progesterone, and produce low levels of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).

Although drugs exist that can block mutant PI3K, breast cancer can outsmart such therapies. What’s more, earlier drugs that attack this pathway shut down multiple isoforms of PI3K, inadvertently disabling pathways that healthy cells rely on. This low level of selectivity has made prior generations of PI3K inhibitors overly toxic. It also made scientists think that the PI3K signaling pathway would be difficult to target.

Researchers pressed on anyway, and developed various inhibitors that selectively target specific PI3K isoforms, and since 2014 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved nearly half a dozen isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors.

To unlock the full therapeutic potential of targeting PI3K and to reach more patients, the key is “treating the right population with ever more selective compounds,” says Jennifer Schutzman, lead medical director at Genentech. “More selective inhibitors may be safer.”

A two-part mechanism

Genentech started working on PI3K nearly two decades ago, focusing mainly on an isoform that is often dysregulated in a common form of breast cancer, called hormone-receptor-positive (HR-positive), HER2-negative breast cancer. Genentech scientists sought to target the PI3K pathway with exquisite precision. To do so, they tweaked chemical structures in a painstaking search for molecules that bind primarily to the PI3K-alpha isoform, while leaving other PI3K isoforms largely untouched. Over about 20 years, the Genentech team gradually developed molecules that bind to the PI3K-alpha isoform with high selectivity.

But the research also led to a big scientific surprise. The researchers discovered that the small molecules do more than bind to the protein—they also induce the cell to digest it.

That discovery marked a turning point, says Marie-Gabrielle Braun, a chemist and senior principal scientist at Genentech who designed the compounds. “It showed that we had done something fundamentally different than what had been achieved with prior generations of these compounds, and it gave us strong confidence that we could potentially have better outcomes in the clinic.”

The dual-action mechanism of this new class of compounds, now known as “protein degraders,” offered unanticipated therapeutic opportunities. It meant that treatments “might be even safer and more efficacious,” Schutzman says. “That’s because you’re taking what you know is a growth-promoting signal and essentially getting rid of it for a more durable period of time. So, you may get increased benefits for patients.”

Expanding use

In addition to treatments for later stages of cancer, Ansley is hopeful that some forms of PI3K protein degraders might offer new treatment options at earlier stages of the disease. In such cases, the aim of treatment is to stop or slow tumor-cell proliferation so that oncologists can regain control of the disease.

To bring these new treatments to the clinic, oncologists can screen for eligible patients by testing for gene mutations that generate the abnormal protein by having biopsy samples tested using next-generation sequencing. They can also collect cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from a blood sample and have it analyzed using one of several commercially available kits that use the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which is less invasive and less expensive, but also less comprehensive, than sequencing.

.

Breast cancer often recurs, in part because breast cancer cells like these can spread rapidly and invade other tissues and organs. Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment