Click the link below the picture

.

I’m fond of saying that the cosmos is like a clock, with many objects and events undergoing cycles that can be measured and understood. Our calendars and clocks, after all, really are based on astronomical processes, such as the turning of Earth and its orbit around the sun.

Some other objects keep a calendar, too, but maybe they don’t check their watch often enough. They run late.

That seems to be the case for the star system T Coronae Borealis, or T Cor Bor for short. Every 80 years or so it dramatically brightens, going from obscurity to one of the 200 brightest stars in the sky in just a matter of hours. That cadence makes each of its flare-ups truly a “once-in-a-lifetime” event. The last time it did this was in 1946, so you might expect that it won’t again until 2026, two years from now. This particular object started showing signs of an impending blowout more than a year ago, however, so astronomers updated their own appointment books for it.

And then nothing—at least, not yet. It’ll blow, of that we’re certain, but it may not do so for another year. Or it could go tonight.

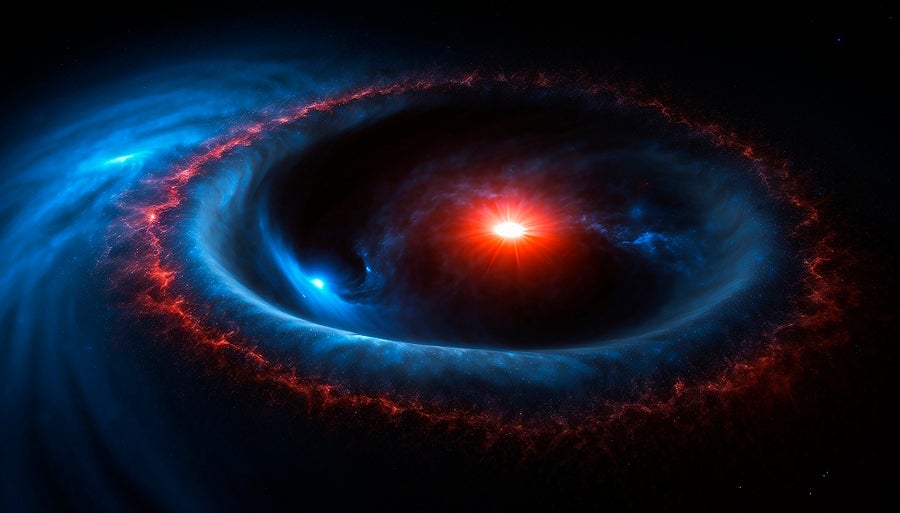

T Cor Bor is a binary star, or two stars that orbit each other. One, usually the brighter of the two, is a red giant, a star that is a little more massive than the sun and at the end of its life. Complicated processes in the star’s core cause the outer layers to swell up and cool. It becomes far more luminous as it grows—emitting much more light—but the cooler gas of its expanding outer layers turns the star red. It’s estimated to be about 75 times wider than the sun, making it more than 100 million kilometers in diameter—big enough that if it was swapped out for our own star, it would stretch nearly to the orbit of Venus.

The other star is far more dead. It, too, started off much like the sun and went through a red giant phase. Over time it blew off its outer layers, revealing the white-hot core—a white dwarf. Only the size of Earth but with more mass than the sun, it’s extremely hot and dense, yet its small stature makes it much fainter than its swollen companion.

Despite its Lilliputian nature, the density of the white dwarf gives it immense gravity. The two stars are so close together, separated by only about 75 million kilometers, that the white dwarf can physically pull material away from the red giant. This puts T Cor Bor in a second stellar category: it’s not just a binary star system but also a symbiotic one.

The red giant’s siphoned-off material moves toward the white dwarf but cannot simply plunge onto it. Because the two stars orbit each other, the infalling material has angular momentum, the tendency of a rotating object to continue rotating. As it moves toward the smaller star, it speeds up that sideways motion, just like water accelerates as it streams down a bathtub drain. This material forms a flattened disk around the white dwarf called an accretion disk. Matter—mostly hydrogen—then falls onto the white dwarf’s surface from the disk’s inner edge.

.

Artist’s concept of a white dwarf star (left) siphoning gas from its larger companion star (right). Scavenged material piling up on the white dwarf can spark a thermonuclear detonation, causing the star to dramatically brighten. Mark Paternostro/Science Source

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment