Click the link below the picture

.

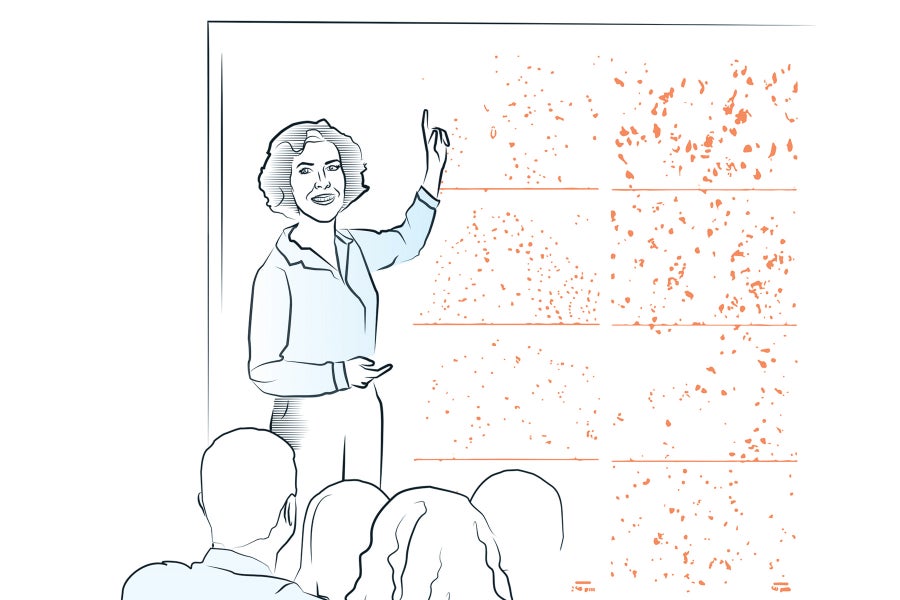

On a spring day in 2011, neuroscientist Cynthia Lemere stood nervously before scientists gathered to appraise the world’s latest research—including hers—at a conference on immune strategies for treating Alzheimer’s disease. Advancing her presentation slides to show stained brain tissue from a recent set of mouse experiments, Lemere circled the pointer around the reddish-brown clumps: protein fragments called amyloid beta that form plaques, a hallmark of the disease. In Lemere’s experiments, mice that received antibody treatment accumulated fewer amyloid plaques than animals receiving placebo.

Some in the audience were skeptical. As Lemere recalls, when she finished her presentation one prominent researcher rose and proclaimed: “It’s not a real thing. It’s a biochemical artifact.”

What that researcher dismissed, others pursued. Lemere and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston have studied this form of amyloid beta since the 1990s; so have researchers in Japan and Germany. Now, the rogue protein is center stage: A drug (donanemab) that targets the molecule recently showed clear benefits in a large clinical study of people with mild Alzheimer’s disease.

Donanemab’s success follows another Alzheimer’s drug, lecanemab (brand name Leqembi), which hit the market in January, and aducanumab (brand name Aduhelm), which got a nod from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2021 after a controversial review. (Aducanumab was withdrawn from the market in 2024.) These are the first new Alzheimer’s treatments since 2003, and the only ones to impede the disease’s progression; earlier drugs only eased symptoms.

The new therapies are revitalizing Alzheimer’s research and renewing hope for millions of families touched by this devastating disease. Yet these treatments carry some risk and a formidable price tag. Translating them from controlled studies to clinical use will require diagnostics that are more scalable and accessible, as well as new training to equip physicians to recognize early-stage disease and decide who is eligible for treatment.

Molecular underpinnings

Alzheimer’s is the most common cause of dementia. It afflicts nearly 7 million people in the United States and more than 30 million worldwide. Older drugs—including donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine—work by prolonging the activity of key chemical messengers in the brain. This enhancement of nerve cell communication offers a temporary boost but does not get at the disease’s molecular roots.

The newest drugs do. They are the long-awaited fruit of the amyloid hypothesis, the theory that identifies amyloid buildup as an essential trigger that disrupts neural circuits, causing mental decline and other signs of dementia decades later. This theory has driven much of the Alzheimer’s disease research and drug development since the 1990s.

Creating drugs to slow this progression requires a deep understanding of how the culprit molecules form and how they become a threat. Before amyloid clumps into disease-associated plaques, it floats in the blood as harmless proteins. Day by day, decade after decade, these amyloid beta peptides are churned out and cleared out, like scores of other proteins processed in the brain as part of normal metabolism.

.

Cynthia Lemere overcame scientific skepticism to show that antibodies against rogue forms of amyloid beta could protect mouse brains from damage. Joelle Bolt

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment