Click the link below the picture

.

All living organisms are made of cells, which are the smallest unit of life. Plants and animals have up to trillions of cells that work together to produce ever more intricate organization and function. Within cells are organelles, or little organs, that do specific jobs. Plant and animal cells have mitochondria, for example, which generate energy, and a nucleus that contains most of the genetic information and acts as a control center. These well-known organelles are enclosed within membranes that maintain their shape and separate them from the cytoplasm, the fluid that fills the cells.

But this textbook account of cells, with its neat division of labor into tidy membrane-bound packages, is incomplete. Not all organelles have membranes, and over the past decade, biologists have come to realize that membraneless organelles—such as tiny droplets of concentrated protein or other biomolecules—may be more plentiful and carry out more diverse tasks in cell function than was previously realized. Scientists call these droplets biomolecular condensates, an analogy to the droplets of water that condense on a cold glass of water on a humid day.

Their physics is somewhat of a mystery. Why don’t these little workers need walls to keep them contained, and how do they keep their elements separate from the cytoplasm around them? By understanding how condensates form and operate, we hope to finally figure out what they do.

This research is still emerging, but scientists think the droplets play vital roles related to gene regulation, cell division, and the transportation of materials within cells. There are even hints that biomolecular condensates are important in cellular processes related to human diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and other neurodegenerative disorders. So far, however, most of the evidence about biomolecular condensates comes from test tube experiments. In the coming years, researchers aim to understand how these droplets act in the more complex environment of a living cell. As we continue to discover new types of condensates and uncover new clues about their purposes, we hope we might even find a universal theory that will describe them all.

Under a microscope, biomolecular condensates look like tiny objects adrift in a sea of cytoplasm packed with organelles and other structures. Though suspended in this liquid, they act like a liquid themselves—they’re spherical in shape and deformable when poked with a micropipette. When two droplets come into contact, they merge into one. The recent discoveries about their possible biological significance have generated interest in how biomolecular condensates form. To a biophysicist like me, this looks like a question of thermodynamics.

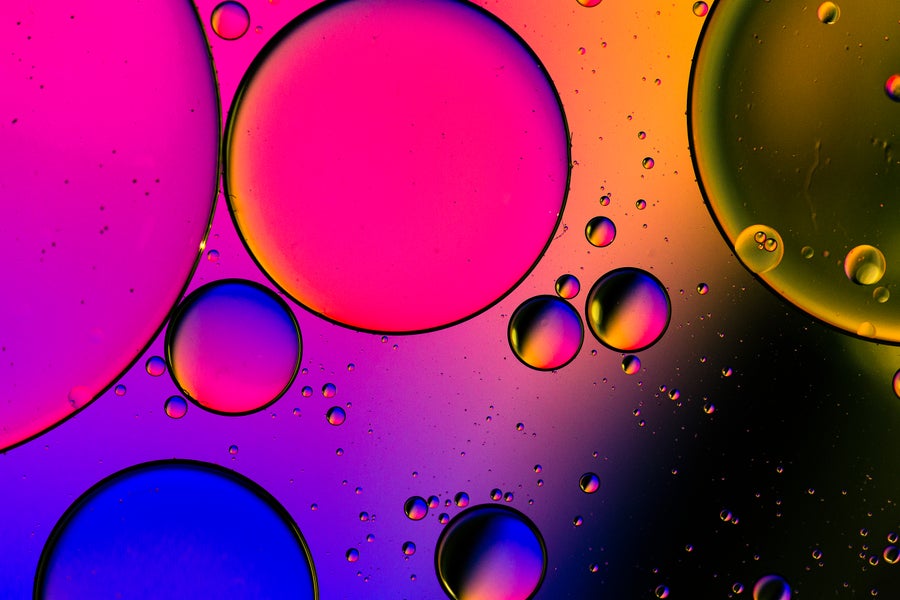

Thermodynamics is the branch of physics concerned with the relationship between heat and other forms of energy. Its principles apply to everything from chemical reactions to meteorology. For our purposes, thermodynamics describes liquid-liquid phase separation—the division of a fluid into two compartments (or phases) with different concentrations and compositions. A classic example is oil and water. If I pour oil into a glass of water, at first the two fluids will mix somewhat. After several minutes, however, they will separate and form two phases: one that is enriched with oil and very little water and another that contains water and very little oil. In contrast, a case where entropy wins is the combination of milk and coffee, which become well mixed.

Thermodynamics tells us that this phase separation results from a competition between entropy and energy. Entropy is the amount of disorder in a system; it favors a uniform mixture of oil and water. Energy includes the energy contained in chemical bonds within each molecule, as well as the energy of interactions between molecules. In this case, the energy for oil molecules to interact with one another is lower than the energy for molecules of oil and water to interact, which drives the oil and water to split into distinct layers. The reduction of energy in the interactions between molecules outweighs the opposing contribution from entropy to stay evenly mixed.

.

coldsnowstorm/Getty Images

coldsnowstorm/Getty Images

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment