Click the link below the picture

.

For new, human-made heavy elements on the periodic table, being “too ‘big’ for your own good” often means instability and a fleeting existence. The more protons and neutrons scientists squeeze together to construct a “superheavy” atomic nucleus—one with a total number of protons greater than 103—the more fragile the resulting element tends to be. So far, all the superheavy elements humans have managed to make decay almost instantaneously. Researchers who synthesized such hefty atoms via a particle accelerator at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, however, have now made a significant stride toward the elusive “island of stability”—a hypothesized region of the periodic table where new superheavy elements might finally endure long enough to buck the trend.

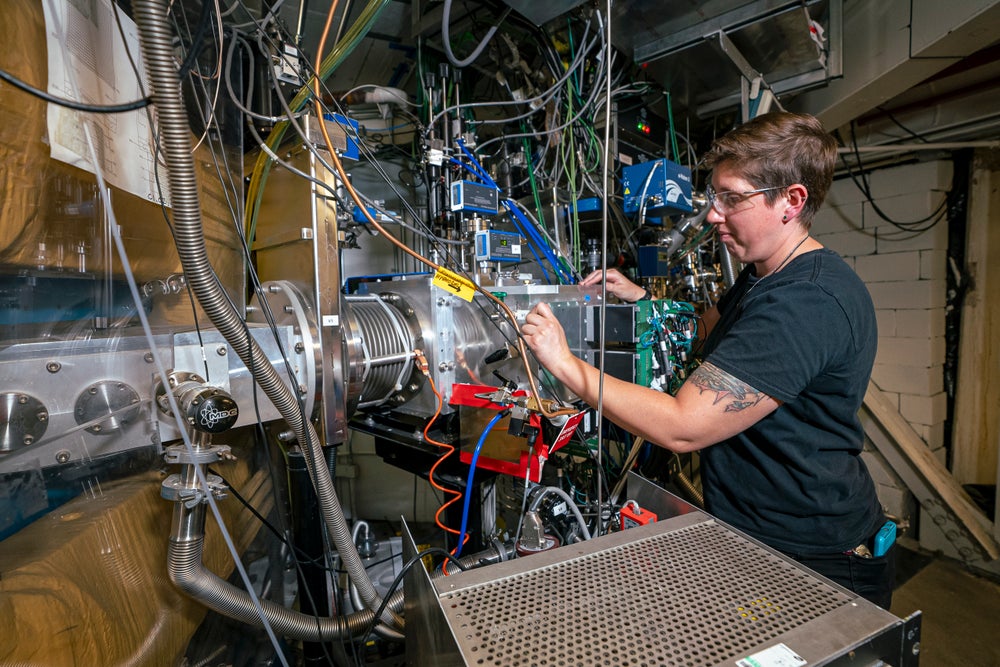

The team successfully forged element 116, livermorium, using a novel method involving titanium 50, a rare isotope that makes up about 5 percent of all the titanium on Earth. By heating this titanium to 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit and channeling it into a high-energy beam, the researchers were able to blast this particle stream at other atoms to create superheavy elements. Although livermorium has been made before using other techniques, this innovative approach paves the way for the synthesis of new, even heavier elements, potentially expanding the periodic table.

“This achievement is truly groundbreaking,” says Hiromitsu Haba, a researcher at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science in Japan, who was not a part of the study. Haba adds that this feat is “necessary to further discover new elements.” The work was presented at July’s Nuclear Structure conference and is currently under review at the journal Physical Review Letters.

The “Simple” Math of Superheavy Fusion

Berkeley Lab is home to the 88-Inch Cyclotron—a device that generates an electromagnetic field to nudge atomic nuclei into shedding some of their surrounding electrons and hurtle at a high speed toward other, stationary atoms. Using these machines, the synthesis of superheavy elements then boils down to simple math: to form an element with 116 protons, you need to fuse two atomic nuclei with that sum total of protons between them. As is often the case with nuclear physics, however, the process is not exactly so simple.

Traditionally, calcium 48 has been the gold-standard isotope for superheavy fusion reactions because of its “doubly magic” nature. Atomic nuclei are surrounded by orbital shells of whirling electrons; nuclei possessing “magic numbers” of protons or neutrons that completely fill in a shell are very stable, and ones with “doubly magic” numbers of both particle types are exceptionally so. But calcium 48’s low proton count limits its utility for creating heavier elements. The heaviest stable element that can be combined with calcium 48 (20 protons) is curium (96 protons), resulting in livermorium (116 protons). While calcium 48 and the heavier berkelium (97 protons) have been used to synthesize element 117, berkelium “is extremely difficult to produce,” says Witold Nazarewicz, chief scientist at the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams at Michigan State University, who wasn’t involved in the new study. “If we want to make most heavier elements, we need a beam with more protons [than calcium 48].”

To make such a beam, the research team turned to titanium 50, attempting to fuse it with plutonium to make livermorium. “Until we ran this experiment, nobody knew how easy or difficult it would be to make things with titanium,” emphasizes Jacklyn Gates, leader of the Heavy Element Group at Berkeley Lab and lead author of the study.

Unlike the doubly magic and highly stable calcium 48, titanium 50 is distinctly nonmagic and lacks extreme stability. It also has a melting point nearly twice that of calcium, making it harder to work with. And the lower stability of titanium 50 atoms decreases the probability of successful fusions, even when collisions occur. “It’s the difference between seeing a synthesized atom every day versus every 10 days or worse,” Gates explains. Despite these challenges, titanium 50 emerged as the next best candidate because it offered hope of creating superheavy elements beyond calcium’s reach.

.

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment