Click the link below the picture

.

Photons are odd little beasts.

They can act like waves. They can act like particles. They are teeny tiny messengers of force. They are carriers of energy.

But most of all, they’re light. When you think of light, you’re thinking of photons. So literally, when you look around you and see, well, anything, your eyes are detecting photons that are emitted by objects like your computer screen or a lamp, photons emitted by those sources that are reflected off other objects, or an absence of photons—a result of something absorbing or blocking them as they travel through space. Because of this, nearly everything we know about objects in deep space is because of light.

Another thing photons are is weird—very, very weird.

In many ways, they behave like waves, similar to those on the beach or in your bathtub when you splash around, with crests and troughs. The distance between crests is called the wavelength, and the amplitude of a wave—its strength, effectively—is the difference in height between the trough and a crest. In a sound wave, that’s related to the volume of the sound. And in light, it’s related to the light’s intensity.

In other ways, photons act like subatomic particles, which can have momentum, spin, and more. It’s very difficult to wrap your head around the idea that light can be a wave and a particle, even at the same time, but quantum mechanics is exceptionally bizarre that way (which is a big reason it took so long to be accepted by scientists as a good model of reality). These properties, however, define light, and they in turn tell us a lot about the objects that emit or reflect it.

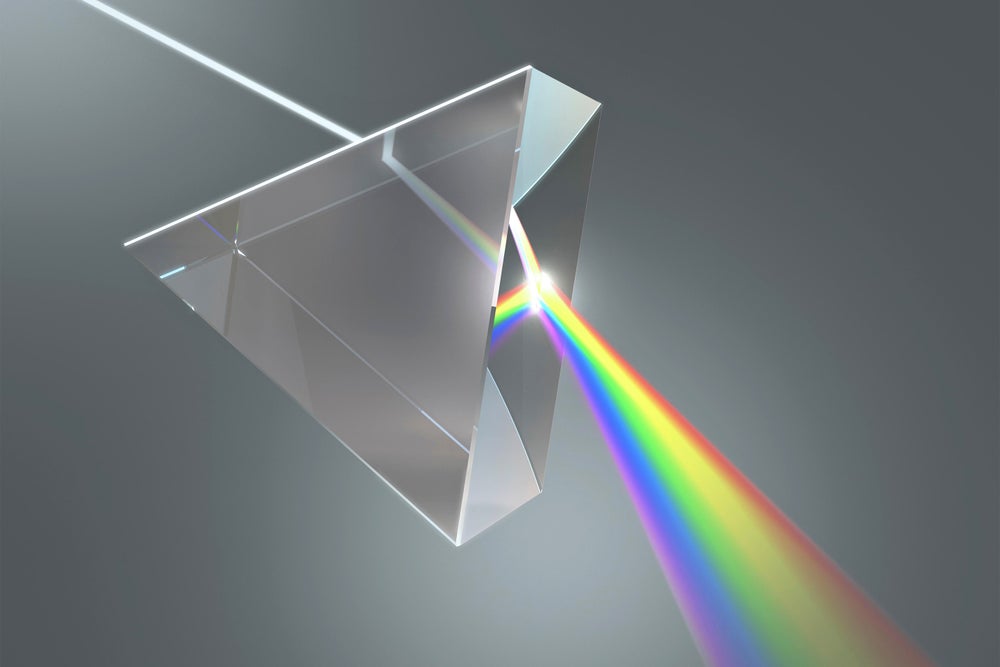

For light, the most fundamental property is the wavelength. That describes how much energy the light has, with shorter wavelength waves having more energy than ones with longer wavelengths. More colloquially, we see this difference in wavelength (or energy) as color. When you see something as violet, for example, you’re seeing light coming from that object with a shorter wavelength. Blue has a slightly longer wavelength, green longer again, then yellow, orange, and finally red, with the longest we see. We can measure the wavelengths of these colors of visible light to determine the range our eyes can detect, and it goes very roughly from 380 nanometers (nm) for violet to about 750 nm for red. (One nanometer is a billionth of a meter.)

An aside: the frequency of light is another fundamental property and is a measure of how frequently the crests pass an observer. It’s equal to the inverse of the wavelength; in other words, the longer the wavelength, the lower the frequency, and vice versa. Scientists use both, usually picking one or the other in their calculations, depending on what makes the math easier or more intuitive.

Our eyes have evolved cells called cones in our retinas that are sensitive to different wavelengths of light. There are three kinds: one detects a small range of wavelengths centered on red, and the others detect ranges centered on green and blue. As light hits those cells, they send signals to the brain, which combines them to create the colors we see.

.

KTSDesign/Science Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo

KTSDesign/Science Photo Library/Alamy Stock Photo

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment