Click the link below the picture

.

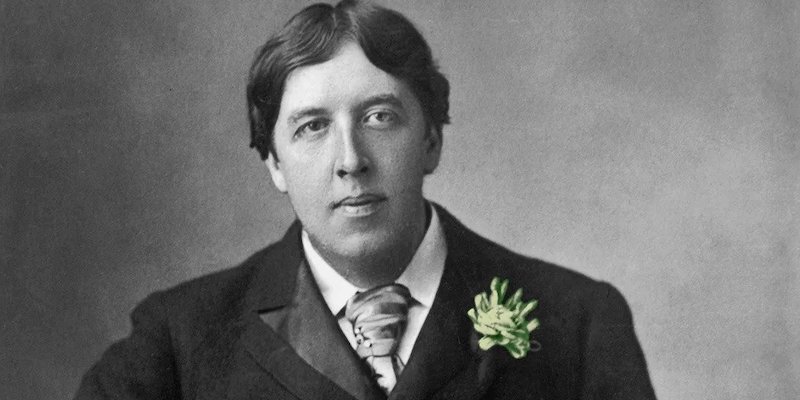

On the evening of January 2, 1882, five men rowed out over the choppy gray waters of New York’s Upper Bay to the SS Arizona, a transatlantic steamer anchored at quarantine a quarter mile off Staten Island. They clambered up an icy rope ladder and spilled onto the deck. Following the directions of the ship’s bemused passengers, they elbowed their way to a twenty-seven year old Irishman clad in a bottle-green ulster, a low-necked white shirt, and a billowing blue silk tie.

“How do you like America, Mr. Wilde?” asked one of the men.

Oscar Wilde burst out laughing in a succession of broad “haw, haw, haws.” He didn’t think it politic to answer: all he had seen of the country was an oil lamp flickering on the horizon.

Wilde was in America to lecture on art. But the main reason his managers had brought him across the Atlantic was to cross-promote a comic opera by W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan. Patience; or, Bunthorne’s Bride parodied London’s “aesthetes”—followers of an artistic craze for blue-and-white china, sunflowers, and peacock feathers. Wilde was a prominent aesthete, so Gilbert and Sullivan’s manager hit upon the idea of using Wilde to educate Americans about the fad. Wilde would create a demand for tickets for Patience, and audiences for Patience would rush to see the genuine article.

The scheme worked. Wilde became a phenomenon. His photographs and book of poems sold in stacks. A constant stream of stories about him flooded the press. Newspaper readers wanted to know more about the real Oscar Wilde, and to meet this desire editors sought interviews with the “Apostle of Aestheticism.”

In the early 1880s interviewing was a peculiarly American custom, and one for which Wilde was unprepared. He confided in the magazine proprietor (and his future sister-in-law) Mrs. Frank Leslie that he had “turned his back” on New York’s “horrible reporters”; she reminded him that it was their business to interview as it was his to lecture, and that he would be better off giving them something to print, else they would be liable to turn on him. Wilde was usually averse to good advice, but he took Leslie’s.

Aware that controversy made the best copy, he steered interviewers away from dull subjects (his favorite color, his definition of aestheticism) and instead slammed what he saw as the architectural travesties of America. The marble mansions of New York’s Fifth Avenue were “so depressing and monotonous”; Chicago’s gothic water-tower, “really too absurd.” He insisted that “a police force for the protection of art ought to be established to prevent the residents of Long Branch from painting their fences in such awful reds and greens.”

.

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

https://lithub.com

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment