Click the link below the picture

.

Ask a woman of reproductive age when her fertility becomes an issue, and she will likely answer: 35. As an OB-GYN in private practice, I see patients who are, for the most part, either pregnant or in some orbit thereof—trying to get pregnant, having trouble getting pregnant, actively trying to prevent pregnancy—and they seem to think there is a threshold midway through one’s 30s that matters very, very much. This may partially result from the fact that women on average are having their first child later in life, so they’re more aware of fertility declining with age. And now, thanks to COVID-19, single and partnered women alike are grappling with delay and uncertainty about whatever timelines they previously held.

Being 35 or older is labeled by the medical community as “advanced maternal age.” In diagnosis code speak, these patients are “elderly,” or in some parts of the world, “geriatric.” In addition to being offensive to most, these terms—so jarringly at odds with what is otherwise considered a young age—instill a sense that one’s reproductive identity is predominantly negative as soon as one reaches age 35. But the number 35 itself, not to mention the conclusions we draw from it, has spun out of our collective control.

Where exactly did the focus on 35 come from? The number was derived decades ago, during a very different reproductive era. Birth control options were limited. Most first pregnancies occurred in women’s 20s. In vitro fertilization was in its infancy.

Most people assume we use age 35 because studies show that things get worse for women at that point. Indeed, early population studies do demonstrate that certain risks, namely the risks of infertility, miscarriage, and chromosomal abnormalities, increase more significantly at age 35. (To be clear, these risks are age-dependent and increase steadily with age generally, but at some point their rate of increase increases, and that inflection point has been pinpointed by some studies at age 35.)

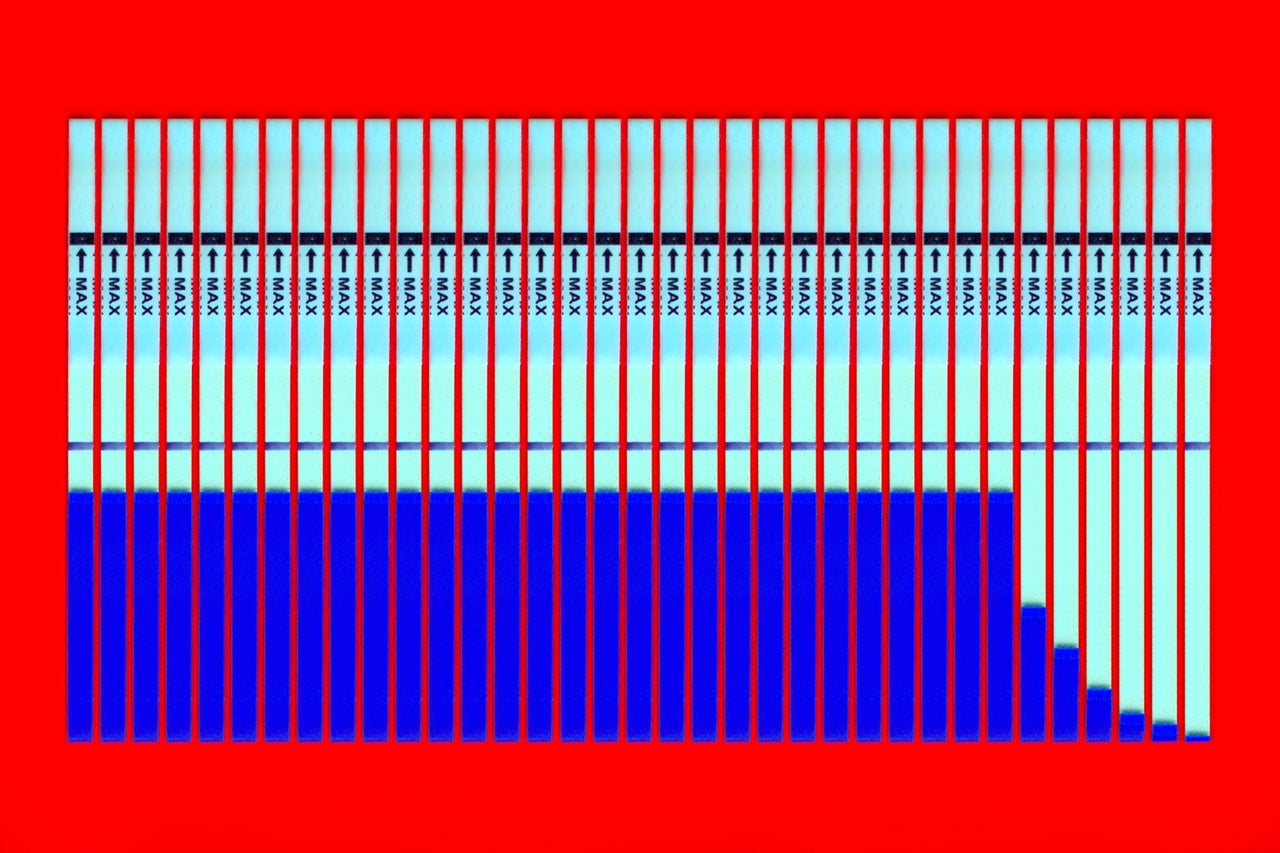

But using age 35 in this way is not as clear cut as it seems. One problem is that it’s an incredibly subjective way of defining what should be objective. The age-related risks of these issues are derived from several large studies, and to look at the tables or graphs of the reported risks is a bit like being administered a Rorschach test: Some will see worrisome numbers starting at age 35, some at 40, some maybe even at younger ages. Moreover, comparing these studies is complicated by their design. For example, when looking at studies regarding Down syndrome risk, some report risk as a function of all live births, while others report it based on amniocentesis results; the amnio risk will appear higher, since some subset of the abnormal pregnancies will miscarry or be electively terminated before the end of the pregnancy could be reached. Put more simply, if you were to ask a dozen professionals to interpret the data and pick one age cutoff whereby to distinguish low-risk from high-risk women, you may very well get a dozen different answers.

.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Getty Images Plus.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Getty Images Plus.

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment