Click the link below the picture

.

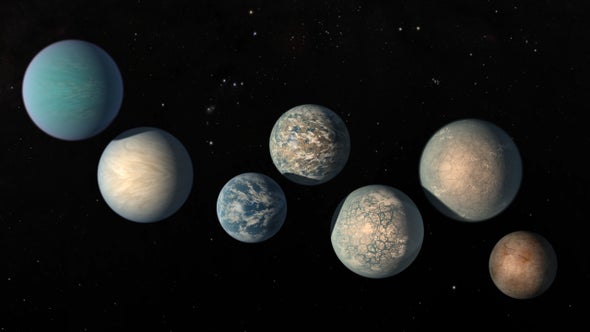

In the constellation Aquarius, invisible to the naked eye, lies a star that might change history. Home to seven mysterious planets—each around the size of our own Earth—the TRAPPIST-1 system is regarded by some as the crown jewel of astronomy’s efforts to find life in the Milky Way. With not one, but three worlds orbiting in the so-called habitable zone, where water can flow and life can thrive, TRAPPIST-1 is one of humanity’s best and brightest opportunities to chase the discovery of a lifetime.

More than science is at stake: what we find—or don’t—on these worlds will shape science forever.

What sets TRAPPIST-1 apart is its striking commonality. At the heart of this system is a small, dim star called a red dwarf. Ranging between 8 percent and 57 percent of the mass of our own sun, red dwarfs quietly make up a remarkable 73 percent of all stars in the galaxy, and are suspected to harbor at least three planets per star. Naturally, this has piqued the curiosity of those who study life in the cosmos—astrobiologists. Could alien life thrive around these small red suns?

The possibility tantalizes the philosopher, but even more so the astronomer: planets around red dwarfs are easier to find than around any other type of star. In fact, the TRAPPIST-1 system was discovered in 2016 with a telescope only two feet across. Because the star is small even by red dwarf standards, its Earth-sized planets stand out easily; when they cross, or transit, the star, they block roughly half a percent of its total light output. For comparison, the Earth only blocks 0.01 percent of our much larger sun’s light when it passes in front of it. In terms of detectability, red dwarfs seem to be the clear winner, and out of 445 red dwarf systems (I asked Jessie Christensen, the scientist who maintains the NASA Exoplanet Archive, what the latest count was), TRAPPIST-1 is one of the brightest that transits, making it a favorite target for astrobiology.

But red dwarfs have a dark side. They are not simply smaller, redder versions of our own well-behaved sun; they are turbulent, active sources of extreme radiation. While Earth experiences violent solar outbursts called coronal mass ejections (CMEs) roughly once every 25 years, a planet that orbits TRAPPIST-1 experiences them weekly. And the bigger the host star, the more powerful the CME. If a planet does not have a strong magnetic field to protect it, a CME can strip away its atmosphere until it is a barren, uninhabitable rock.

In addition, red dwarfs are born hot, and cool over time. This means that a planet may have its water inventory boiled away before it gets the chance to settle into the habitable zone, or that a planet may begin its life habitable before freezing over. Finally, red dwarf planets live very close to their star, and when two things in space orbit close together, one will eventually come to face the other—the way the same side of the moon is always facing the Earth. In the case of TRAPPIST-1’s planets, this means that one hemisphere may experience eternal daytime, and the other, eternal night: perhaps unideal conditions for life to evolve.

.

This illustration shows the seven Earth-size planets of TRAPPIST-1, an exoplanet system about 40 light-years away, based on data current as of February 2018. The image shows the planets’ relative sizes, but does not represent their orbits to scale. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt, T. Pyle (IPAC)

This illustration shows the seven Earth-size planets of TRAPPIST-1, an exoplanet system about 40 light-years away, based on data current as of February 2018. The image shows the planets’ relative sizes, but does not represent their orbits to scale. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt, T. Pyle (IPAC)

.

.

Click the link below for the article:

.

__________________________________________

Leave a comment